Brain Health for Everyone

Building Inclusive Dementia Care Across the Lifespan

Beth A. Marks, Ph.D., FAAN, Jasmina Sisirak, Ph.D., MPH, Matthew P. Janicki, Ph.D., & Kathryn P. Service, RN, M.S., FNP-BC

Why Brain Health Must Include Everyone

Brain health is often discussed as a medical concern, shaped by diagnoses, treatments, and clinical settings. Yet for many people, especially those with intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD), brain health is experienced far beyond the walls of a clinic. It is lived out in homes, workplaces, schools, and community spaces, in relationships with family members, support staff, neighbors, and friends. As people with IDD live longer, questions about aging, memory, and dementia are becoming increasingly important, not only for healthcare systems but for communities that have a shared responsibility to ensure dignity, inclusion, and quality of life across the lifespan.

Historically, conversations about “healthy aging” have largely taken place within gerontology and public health, while the needs and experiences of people with IDD have been addressed within separate disability service systems. This separation has created gaps in care, understanding, and visibility. Adults with IDD are often missing from public health data, large surveys, and policy planning efforts. When people are not counted, they are less likely to be considered in funding decisions, workforce training, and service design. Over time, this invisibility contributes to delayed recognition of health concerns, limited access to preventive care, and uneven availability of dementia-capable supports.

This article advances the idea that brain health must be understood as a shared public good that benefits individuals with IDD and their families, caregivers, service systems, and their communities. By placing people with IDD at the center of brain health promotion and dementia care, we can strengthen equity, improve coordination across systems, and build more inclusive approaches to aging that reflect the full diversity of human experience.

Rethinking Brain Health Through a Human Lens

Brain health is often reduced to narrow measures of memory, attention, or cognitive performance. While these are important, they capture only part of what it means to live well. For people with IDD, brain health is deeply connected to communication, relationships, routines, and opportunities to participate in meaningful activities. It is shaped by how environments are designed, how information is shared, and how much control individuals have over their own lives.

A broader understanding of brain health recognizes that people learn, express themselves, and engage with the world in many ways. Some communicate through speech, others through gestures, pictures, technology, or familiar routines. Some thrive in structured environments, while others benefit from flexible, relationship-based supports. An inclusive approach does not treat these differences as deficits to be corrected, but as variations to be respected and supported.

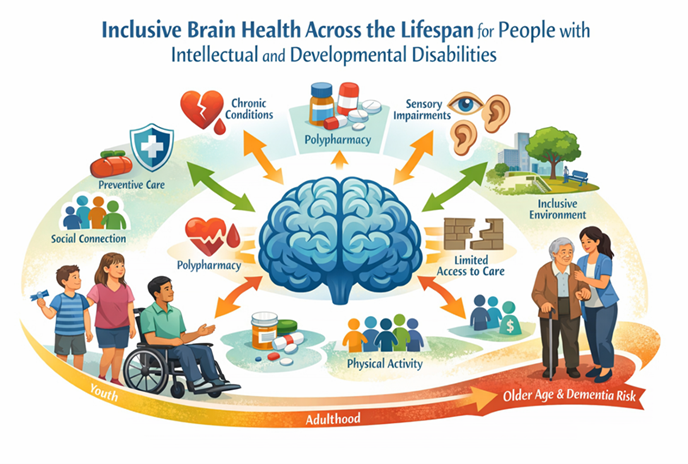

Brain health is framed as a life-course process shaped by interconnected medical, social, and environmental influences from youth through older age. The figure illustrates this framework by showing how preventive care, social connection, physical activity, and inclusive environments can strengthen cognitive well-being, while factors such as chronic conditions, sensory loss, polypharmacy, and limited access to care increase vulnerability. The lifespan progression depicted in the figure underscores that early, sustained, and coordinated supports are essential for promoting resilience and reducing dementia risk among people with intellectual and developmental disabilities.

A broader understanding of brain health recognizes that people learn, express themselves, and engage with the world in many ways. Some communicate through speech, others through gestures, pictures, technology, or familiar routines. Some thrive in structured environments, while others benefit from flexible, relationship-based supports. An inclusive approach does not treat these differences as deficits to be corrected, but as variations to be respected and supported.

This perspective also challenges assumptions about what “successful aging” looks like. For many people with IDD, aging well may mean maintaining familiar routines, staying connected to trusted caregivers, and continuing to participate in community life in ways that feel safe and meaningful. Brain health, in this sense, is as much about belonging and autonomy as it is about clinical outcomes.

Dementia, Disability, and the Question of Equity

For some adults with IDD, particularly individuals with Down syndrome, the risk of developing dementia is higher, and often, early signs are more noticeable at younger ages than in the general population. This biological reality intersects with long-standing social and structural barriers. People with IDD may face challenges accessing regular healthcare, preventive services, and specialized assessments. Providers may have limited training in recognizing cognitive change in individuals who already have lifelong differences in learning or communication.

As a result, early signs of dementia can be overlooked, misinterpreted, or dismissed. Changes in memory, mood, or daily functioning may be attributed to the person’s disability rather than recognized as indicators of a new health condition. This phenomenon, sometimes called “diagnostic overshadowing,” can delay appropriate evaluation and support, leaving individuals and families without clear guidance during a critical period.

Equity in dementia care is not only about access to medical services. It also involves the availability of information in plain language, culturally responsive supports, and environments that accommodate a wide range of abilities. When these elements are missing, people with IDD and their families may experience a form of “double disadvantage,” in which the challenges of disability are compounded by the challenges of aging and cognitive decline.

The Central Role of Caregivers

Caregivers, whether family members, friends, or paid support staff, are the backbone of brain health for people with IDD. They are often the first to notice subtle changes, such as a person who becomes less interested in favorite activities, struggles with routines that once came easily, or shows new patterns of confusion or frustration. These early observations are critical for identifying health concerns and seeking timely support.

Yet caregivers frequently navigate a complex and fragmented landscape of services. Aging systems, disability services, and healthcare providers may operate under different rules, funding streams, and expectations. Families can find themselves acting as coordinators, advocates, and translators, trying to bridge gaps between systems that do not always communicate with one another.

“For families, dementia in a loved one with a lifelong disability is not just a medical journey, it is a navigation of fragmented systems that too often fail to speak to one another.”

As cognitive changes progress, the demands on caregivers increase. Daily tasks may take longer and require more patience. Emotional strain can grow as families and staff cope with uncertainty and loss. Without adequate support, caregivers are at risk for burnout, physical health problems, and social isolation. When caregivers are supported through education, coordinated care, and opportunities for rest, people with IDD are more likely to remain in stable, familiar environments and maintain a higher quality of life.

Visibility, Data, and the Power of Being Counted

One of the most significant barriers to inclusive brain health is visibility. Many people with IDD are not consistently identified in public health data, surveys, or administrative systems. When people are not visible in the data, their needs are more easily overlooked in policy decisions, funding priorities, and program design.

Data shape how problems are defined, and which solutions are pursued. If dementia prevalence among people with IDD is not accurately measured, resources may not be allocated to develop appropriate services or train providers. If caregivers’ experiences are not captured, their needs may remain unaddressed.

Inclusion begins with a simple but powerful principle: people with IDD must be built into data systems and programs from the start. This means using identifiers that recognize disability status, designing accessible surveys, and involving people with IDD and their families in shaping how information is collected and used. When data reflect the full diversity of the population, they can serve as a tool for accountability and equity rather than a source of exclusion.

“When people with intellectual and developmental disabilities are missing from the data, they are often missing from the plan. Inclusion must be built into brain health efforts from the very beginning and not added later as an afterthought.”

Community Partnerships and Systems Change

No single organization can create inclusive brain health on its own. The most promising efforts bring together partners from across sectors: disability services, public health departments, aging networks, healthcare providers, universities, and community organizations. Each brings unique expertise and perspectives that, when combined, can create stronger and more responsive systems of care.

These partnerships can help align outreach efforts, reduce service duplication, and create clear pathways for families seeking support. They also enable sharing training resources, developing a common language, and coordinating responses to emerging needs. In many communities, trusted organizations, such as faith groups, cultural associations, and neighborhood programs, play a vital role in reaching families who may not be connected to formal service systems.

By working together, partners can design programs that reflect local cultures, languages, and values. This community-based approach helps ensure that brain health promotion and dementia care are not abstract concepts, but practical, accessible supports embedded in everyday life.

A Model in Practice: The HealthMatters™ Healthy Brain Initiative

The HealthMatters™ Healthy Brain Initiative at the University of Illinois Chicago offers an example of how inclusive brain health can be put into practice. Grounded in public health principles, the initiative focuses on building bridges between disability services, aging networks, and healthcare systems.

Rather than concentrating solely on producing educational materials, the initiative emphasizes systems change. It encourages organizations to examine who is included in planning and decision-making, what data guide their priorities, and how training and outreach are designed. This approach recognizes that lasting change requires shifts in structures and relationships, not just information.

Through partnerships with state and local agencies, community organizations, and service providers, the initiative raises awareness of early signs of cognitive change, strengthens workforce skills, and develops plain-language resources for families and caregivers. By embedding these efforts within existing public health and community programs, the initiative helps make brain health a routine part of community life.

Building a Prepared and Compassionate Workforce

A key element of inclusive brain health is workforce development. Many professionals in healthcare, social services, and public health receive limited training in working with people with IDD, and even less training in recognizing and supporting dementia in this population.

This gap can lead to missed opportunities for early intervention, misinterpretation of symptoms, and frustration for families seeking help. Training programs that focus on practical skills, such as effective communication, recognizing changes from a person’s baseline, and coordinating across systems, can improve confidence and competence among providers.

Community-based training models, which bring education into real-world settings, can help ensure that knowledge is translated into practice. When professionals understand both the clinical and social dimensions of brain health, they are better equipped to support individuals and families in meaningful, respectful ways.

Engaging the Public and Reducing Stigma

Public understanding of dementia and disability plays a powerful role in shaping experiences of aging. Stigma, fear, and misunderstanding can lead to social isolation and reduced opportunities for participation. Inclusive public education can help shift these narratives.

Clear, accessible information shared through trusted community channels, including local organizations, online platforms, and public events, can raise awareness about brain health and encourage early help-seeking. Stories that highlight the strengths, contributions, and voices of people with IDD and dementia can challenge stereotypes and promote empathy.

Public engagement is most effective when it reaches beyond those already connected to formal systems. Outreach to rural communities, culturally diverse groups, and families who may be hesitant to seek services can help ensure that inclusion is not limited to a narrow segment of the population.

Looking Forward: A Shared Path for Healthy Aging

The future of inclusive brain health depends on sustained commitment across systems and communities. Building partnerships, improving data collection, training a prepared workforce, and engaging the public are interconnected efforts that reinforce one another.

When people with IDD and their caregivers are included in planning and decision-making, programs are more likely to reflect real-world needs and priorities. When data accurately capture experiences and outcomes, resources can be directed where they are most needed. When professionals are trained to work confidently across disability and aging contexts, care becomes more coordinated and responsive.

Ultimately, inclusive brain health is more than preventing or managing dementia. It is about creating communities where people with IDD can age with dignity, connection, and opportunity. It is about recognizing that brain health is not a specialized concern for a few, but a shared responsibility that touches every family and every neighborhood.

“Inclusive brain health is not a specialty service. It is a community commitment to dignity, access, and belonging across the entire lifespan.”

Belonging Across the Lifespan

At its core, the movement toward inclusive brain health reflects a simple but profound belief that every person’s way of thinking, communicating, and living in the world adds value to the communities we share. When people with intellectual and developmental disabilities are included by design, brain health becomes a shared public good to support not only individuals, but families, caregivers, and society as a whole.

Brain health promotion must include people with IDD by design. When people with IDD are excluded from public health planning, data, and programs, dementia risks go unrecognized and care inequities grow.

Dementia risk is real - but not inevitable. Adults with IDD, especially those with Down syndrome, face a higher dementia risk, but many contributing factors are modifiable through accessible health promotion, prevention, and early detection.

Diagnosis and care require a disability-affirming lens. Dementia in people with IDD is often missed or delayed due to diagnostic overshadowing, inappropriate tools, and lack of provider training on intellectual and developmental disabilities, which makes longitudinal, person-centered assessment essential.

Systems must work together, not in silos. Inclusive dementia care relies on strong partnerships among aging, disability, public health, and community systems to ensure coordinated services for individuals and their families.

Inclusion strengthens care for everyone. Designing brain health strategies that work for people with IDD builds more equitable, effective, and dementia-capable systems for all older adults.

About the Authors:

Dr. Beth Marks and Dr. Jasmina Sisirak are the Co-Directors for the HealthMatters™ Program and the CDC-Funded Healthy Brain Initiative (Award 1 NU58DP006782-01-00) at the University of Illinois Chicago

Dr. Matthew P. Janicki and Ms. Kathryn P. Services are members of the Board of Directors for the National Task Group on Intellectual Disabilities and Dementia Practices.

This article reflects a five-year partnership between the HealthMatters™ Program at the University of Illinois Chicago and the National Task Group on Intellectual Disabilities and Dementia Practices (NTG), supported by the CDC-Funded Healthy Brain Initiative for People with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities (Award 1 NU58DP006782-01-00). Their joint work across public health, aging, and disability systems, including their 2025 article in The Gerontologist, “Dementia Care for People with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities: A Public Health Framework” (65[S1], S60–S67), forms the foundation for this HELEN feature.