The Ethical Algorithm: Navigating AI and its Applications in the Lives of People with IDD – Part 5

What is AI Anyway? Walking Through History and Cutting Through the Jargon

AI as a Partner: Enhancing Health Supports with People with Disabilities

Addressing Bias and Ableism: Centering Disability Voices in AI Development

Real Risks, Real Voices: What People with Disabilities Say About AI

By David A. Ervin, BSc, MA, FAAIDD and Douglas Golub, BA, MS, SHRM-CP, DrPH(C)

This is the final installment of a five-part series on artificial intelligence (AI) and its emerging role in home and community-based services and healthcare for people with intellectual and/or developmental disabilities (IDD). This final article explores how AI can be implemented in ways that are ethical, inclusive, and practical, drawing on lessons from our previous installments, the current state of technology, and real-world use cases to show how targeted, well-designed applications can maximize benefits while minimizing risks.

What We Know & What We’ve Learned

A recent AP–NORC poll shows that AI use is becoming commonplace in everyday life, with roughly 60% of U.S. adults using it primarily for searching information. About 40% of respondents reported using AI at work, for brainstorming, drafting emails, or generating images. About 26% of respondents reported using these tools for shopping, while approximately 15% reported using AI tools for social or companionship interactions (O’Brien, 2025). There are substantial challenges to a reliable understanding of the uptake of AI among people with intellectual and/or developmental disabilities (IDD) (United Nations, 2024; Zentel et al., 2024), although there is little doubt that it is consequentially less than among people who do not have an IDD.

The Ethical Algorithm series has explored the world of generative artificial intelligence (AI) that has become more accessible since the 2022 release of ChatGPT, one of a growing number of large language model (LLM) platforms that are combining to make AI ever more ubiquitous. We have touched on the history of AI, as well as its evolution into the 21st Century. We began by breaking down what AI is and, as importantly, what it isn’t, even as we’ve acknowledged that distinctions between actual artificial intelligence from ever advancing and impressive modern technologies are diffuse. We’ve examined bias and ableism in AI design in detail and depth, calling out significant ethical considerations and calling out loudly for the absolute necessity of including disability voices. We have explored AI’s potential in enhancing both long-term services and supports and in healthcare. Perhaps most significantly, we spoke to, asked questions of, and listened carefully to people with IDD about their hopes and fears, and their vision for AI in their lives.

Across our research and central to all of these conversations, one principle stands out: the future of computing is conversational, and AI must be designed and implemented with people with IDD as part of the conversation. El Morr and colleagues (2024) examine current research in AI and people with disabilities and offer important recommendations that should anchor application of AI to supporting people with IDD. They echo what we heard from the advocate leaders, people with lived experience featured in last month’s installment. (For readers of parts 1-4 of this series, these recommendations will ring familiar. At the risk of redundancy, we offer them verbatim below nevertheless as an expression of their absolute priority.)

1. Shift Towards a Social Model of Disability: AI research and development needs to prioritize the social model of disability, understanding that disability is more than just a medical condition and is influenced by the interaction between individuals and their environment. This approach would foster the creation of AI solutions that address societal barriers and promote inclusivity.

2. Promote Interdisciplinary Collaboration: AI researchers, disability experts, and individuals with disabilities need to work together to guarantee that AI technologies are created and utilized in ways that truly support and empower people with disabilities. This cooperation should include individuals with disabilities in every phase of AI development, from initial idea generation to the testing and implementation stages.

3. Address Bias and Discrimination: AI researchers need to implement actions to identify and mitigate biases in AI algorithms and datasets. This includes ensuring diverse representation in training data, employing fairness-aware machine learning techniques, and continuously monitoring AI systems for discriminatory outcomes.

4. Prioritize Privacy and Security: Researchers and developers must establish and uphold strict privacy and security guidelines for AI systems that gather and analyze the personal data of people with disabilities. This entails acquiring informed consent, ensuring transparency in data utilization, and implementing strong security measures to safeguard against data breaches.

5. Focus on Accessibility and Usability: Designing AI-powered tools and applications that are accessible and usable for people with diverse disabilities is crucial. This involves integrating features like screen readers, voice recognition, and alternative input methods to guarantee that everyone can take advantage of AI technologies.

6. Invest in Education and Training: It is imperative to ensure that education and training programs for AI researchers, developers, and practitioners focus on disability rights, accessibility, and inclusive design. This will contribute to increasing awareness and building skills for creating AI solutions that are fair and advantageous for everyone in the community.

7. Advocate for Policy and Regulatory Frameworks: Advocacy groups should advocate for the creation and enforcement of policies and regulations that support the ethical and responsible application of AI for individuals with disabilities. This involves guaranteeing that AI tools are employed to uphold human rights, advance social equity, and prevent the worsening of current disparities.

Inclusion, transparency, and real-world relevance are not optional; they are the foundation of ethical AI.

Specific Use Cases

“A use case is a narrative describing how [it] will be used to accomplish a goal. Use cases designed with a goal in mind are a valuable planning tool. A well-crafted use case communicates the functional requirements to inform the technical planning” (Massachusetts eHealth Institute, 2025, para. 1-2). Much like service planning for people with IDD, clearly defining what we want AI to do, how it can be trusted, what safeguards are in place and/or needed, and the outcomes we expect helps us anticipate risks, establish guardrails, and ultimately achieve results that align with our goals, needs, and values. Rather than viewing AI as something amorphous, it’s more effective to focus on specific use cases to guide clear requirements, planning, and expectations.

“The promise of AI for all people lies in enhancing independence while building tools to leverage interdependence, improving communication, and reducing barriers to full inclusion of and engagement with marginalized communities. ”

Modern support technologies, including AI, have a critical place in long-term services and supports and in healthcare for people with IDD. One of the clearest lessons from both technology adoption and disability advocacy is that being intentional and specific in planning, rather than having vague or generic approaches, can deliver meaningful benefits. “Person-centered planning, which allows people to tailor their services to their individual preferences, was linked to positive outcomes in community living. These positive outcomes include: People enjoyed increased participation in the community, they felt more in control of their life, and they were more satisfied with how they spent their days” (Caldwell, 2025, p. 6).

This Ethical Algorithm series explored the risks of intentional or unintentional sharing of personal data with large language models. We have urged design with the current best practices around an “AI Bill of Rights,” including safe and effective systems, protection against algorithmic discrimination, data privacy, notice and explanation of AI use, and human alternatives, consideration, and fallback (Johnson, 2022), the door is open to the benefits of use cases that people want. There are many.

AI-powered communication tools can translate speech to text in real time, making it possible for people to communicate without using a keyboard. Accessible telehealth platforms that automatically adjust visual, auditory, and cognitive features can make healthcare experiences more self-determined and inclusive. Patterns and categories in service notes can sometimes help identify what is working and what isn’t with services and supports. AI-driven medication reminders delivered in plain language can improve adherence and reduce some of the risks and consequences of medication errors. Smart transportation planners account for accessibility, which can expand a person’s mobility, and smart home support safety systems that detect falls or hazards can support independent living without sacrificing privacy. At the intersection of AI and robotics resides more potential benefit to people with IDD, particularly in healthcare through demonstrably improved diagnostics and treatment (Afkhami et al., 2025), and even through the development of companionship and cognitive stimulation models (Sukhadeve, 2025).

AI can also improve systems and policy. Chatbots designed to guide people through Medicaid waiver applications in plain language, and paired with real-time eligibility checks, can make benefits more accessible while reducing administrative errors, causing gaps in essential coverage. Similarly, predictive analytics can identify health and other needs like housing or transportation, access to health service and wellness resources, and other critical social determinants of health, thereby helping policymakers allocate resources more equitably. These examples demonstrate that when AI is deployed with specificity, accessibility, and safeguards in mind, it can directly advance independence, equity, and quality of life.

A Positive Path Forward

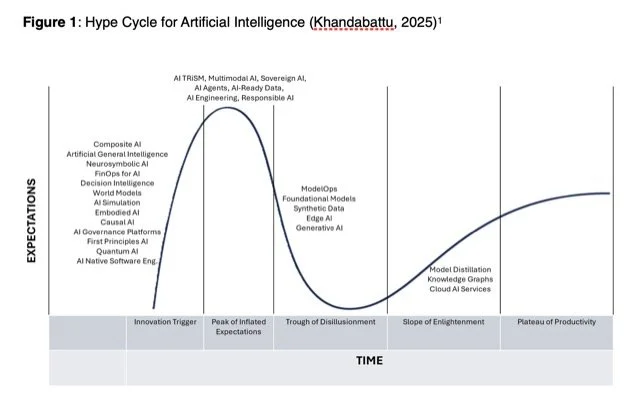

Gartner’s Hype Cycle (Fenn, 1995) is a model that describes the typical path new technologies take from their introduction to mainstream adoption. It maps technology adoption through five stages: Innovation Trigger (early emergence), Peak of Inflated Expectations (intense hype), Trough of Disillusionment (declining enthusiasm), Slope of Enlightenment (growing practical understanding), and Plateau of Productivity (widespread, proven use). In the 2025 Gartner Hype Cycle for Generative AI, most technologies like the Large Language Models explored in this series are currently sitting at the “Peak of Inflated Expectations” phase, meaning hype is at its highest, but widespread, sustainable adoption is still ahead (Khandabattu, 2025).

Figure 1: Hype Cycle for Artificial Intelligence (Khandabattu, 2025)[1]

[(1)The visualization depicted in Figure 1 is inspired by the concept of technology hype cycles, popularized by Gartner, Inc. It is not affiliated with or endorsed by Gartner. The positioning of technologies reflects a synthesis of current industry analysis and is not derived from Gartner's proprietary "Hype Cycle for Generative AI, 2025" research.]

This means now is the window for development of AI and piloting new technologies, keeping laser, unrelenting focus on ethics and full inclusion of people with IDD. Technology vendors that overpromise and underdeliver will lose credibility; those that act carefully and transparently will be best positioned when the technology reaches the Plateau of Productivity, with widespread, proven use.

The promise of AI for all people lies in enhancing independence while building tools to leverage interdependence, improving communication, and reducing barriers to full inclusion of and engagement with marginalized communities. If developed and used safely and ethically, AI can help design more appropriate services and supports, make communications more accessible, and empower people with IDD to have a stronger voice in their world.

We are at a pivotal—and exciting—moment in history, one that must include fully people with IDD. The Peak of Inflated Expectations can either lead to disappointment and mistrust or form a solid foundation for intentional, inclusive innovation. By centering lived experience, defining clear, transparent, and safe use cases, and committing to ironclad ethical principles, we can improve the possibility that when AI reaches the Plateau of Productivity, it won’t just be about efficiency, it will be all about equity, dignity, and opportunity for all.

Citations:

Afkhami, A., Benesty, J., Bernardo, D., Chandrashekhar, S., Cristea, N., Heeg, A., Kouris, I., Neiser, J., Nwokah, E., Thekkepat, S., Trommer, G., & Wilson, A. (2025, February 5). How digital and Ai Will Reshape Health Care in 2025. BCG Global. https://www.bcg.com/publications/2025/digital-ai-solutions-reshape-health-care-2025

Caldwell, J., Chong, N., & Pickern, S. (2024, April). Association of person-centered planning with improved community living outcomes (Research Policy Brief). Center for Community Living Policy, Brandeis University. https://heller.brandeis.edu/community-living-policy/research-policy/pdfs/briefs/association-of-person-centered-planning-w-improved-community-living-outcomes.pdf

El Morr, C., Kundi, B., Mobeen, F., Taleghani, S., El-Lahib, Y., & Gorman, R. (2024). AI and disability: A systematic scoping review. Health Informatics Journal, 30(3). https://doi.org/10.1177/14604582241285743

Fenn, J. (1995). Understanding Gartner’s hype cycle. Gartner, Inc.

Johnson, K. (2022, October 4). Biden’s AI Bill of Rights is toothless against big tech. Wired. https://www.wired.com/story/bidens-ai-bill-of-rights-is-toothless-against-big-tech/

Khandabattu, H. (2025, July 8). The 2025 Hype Cycle for Artificial Intelligence goes beyond GenAI: The focus is shifting from the hype of GenAI to building foundational innovations responsibly. Gartner. https://www.gartner.com/en/articles/hype-cycle-for-artificial-intelligence

Massachusetts eHealth Institute. (2025). HIE use case toolkit. Massachusetts Technology Collaborative. Retrieved August 12, 2025, from https://mehi.masstech.org/hie-use-case-toolkit

O’Brien, M., & Sanders, L. (2025, July 29). How US adults are using AI, according to AP-NORC polling. Associated Press. Retrieved August 12, 2025, from https://apnews.com/article/229b665d10d057441a69f56648b973e1

Sukhadeve, A. (2025, July 30). How ai is Transforming Healthcare in 2025. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/councils/forbesbusinesscouncil/2025/07/30/how-ai-is-transforming-healthcare-in-2025/

United Nations. (2024, February 12). Building an accessible future for all: Ai and the inclusion of persons with disabilities. Regional Information Centre of Western Europe. https://unric.org/en/building-an-accessible-future-for-all-ai-and-the-inclusion-of-persons-with-disabilities/

Zentel, P., Hammann, T., Engelhardt, M., & Kupitz, C. (2024). At the Limits of Feasibility: AI-Based Research for and with People with Profound Intellectual and Multiple Disabilities. Journal of Mental Health Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 17(3), 173–177. https://doi.org/10.1080/19315864.2024.2333240

About the Authors

David Ervin has worked in the field of intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD) for nearly 40 years in the provider community mostly, and as a researcher, consultant, and ‘pracademician’ in the US and internationally. He is currently CEO of Makom, a community provider organization supporting people with IDD in the Washington, DC metropolitan area. He is a published author with nearly 50 peer-reviewed and other journal articles and book chapters, and more, and he speaks internationally on health and healthcare systems for people with IDD, organization development and transformation, and other areas of expertise.

David’s research interests include health status and health outcomes experienced by people with IDD, cultural responsiveness in healthcare delivery to people with IDD, and the impact of integrating multiple systems of care on health outcomes and quality of life. David is a consulting editor for three scientific/professional journals, and serves on a number of local, regional and national policy and practice committees, including The Arc of the US Policy and Positions Committee. David is Conscience of the Field Editor for Helen: The Journal of Human Exceptionality, Vice President of the Board of Directors for The Council on Quality and Leadership (CQL), and Guest Teaching Faculty for the National Leadership Consortium on Developmental Disabilities.

Doug Golub is the Principal Consultant at Data Potato LLC and a Doctor of Public Health (DrPH) student at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. While earning his Master of Science at Rochester Institute of Technology, he worked as a direct support professional, an experience that shaped his career in human services and innovation. He co-founded MediSked, a pioneering electronic records company for home and community-based services, which was acquired after 20 years of impact. Doug has also held leadership roles at Microsoft’s Health Solutions Group and is a nationally recognized thought leader on data, equity, and innovation. He serves on the boards of the ANCOR Foundation and FREE of Maryland.