Diagnostic Overshadowing: The Pitfalls of Prejudicial Thinking

By Emily Johnson, MD

“A misleading symptom is misleading only to one able to be misled.” - Sir Heneage Ogilvie

I keep a list of my patients who have passed away. Currently, the names reside on a sticky note in my office – I keep promising myself to upgrade the display. I try to play a small part in keeping each of their memories alive. There’s one patient on the list whose death I continue to wonder about. In the months leading up to it, I saw him many times, knowing there was something wrong but not knowing what. He was non-speaking, so it was always hard to know what he was feeling, hard to know what direction to take a workup. He had a variety of abnormal labs, but there was no obvious pattern. I spoke with other doctors to get input and ideas of what the underlying diagnosis could be. I had assumed I had time to sort it all out. It crushed me when he passed, not only because I truly loved him as a patient, but also because I had to face the fact that I missed a diagnosis, that perhaps someone better or smarter might have figured it out. The family opted not to do an autopsy, so I will never know what I missed. A physician’s job is to diagnose, but inevitably, whether we want to admit it or not, we all miss from time to time.

There are countless reasons patients go undiagnosed or misdiagnosed, and we are fortunate when we have the opportunity to identify and learn from the experience. Upon first thought, most would probably assume that all missed diagnoses arise from knowledge-based errors, in which a clinician just does not know enough to identify the underlying diagnosis, as in the story described above. Knowledge-based errors are a clear issue and one that clinicians spend their careers working to avoid. Medical and dental school, residencies, and fellowships are all designed to help us avoid knowledge-based errors. Assuming the correct diagnosis is ultimately discovered, knowledge-based errors are also some of the easiest to identify and learn from. Unfortunately, they are far from the only types of errors that lead to missed diagnosis.

On the other end of the spectrum, missed diagnoses also arise from a variety of bias-based errors. In these cases, a clinician has the sufficient underlying knowledge to make the correct diagnosis but is unable to do so because of some underlying bias, which may be in relation to a group of people or simply due to the way in which information was presented and an inability to get themselves out of a certain train of thought. As these biases are, by nature, not something the clinician is consciously aware of, they are much more difficult to identify and learn from. Undoubtedly, we have all made these errors, many of which we never even realize. These are also errors that likely disproportionately affect marginalized patients.

Not long ago, a patient of mine with Down syndrome came to my office with staff from his group home to address “sundowning.” He had carried a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease for a few years at the time, originally diagnosed by an outside provider. When his group home staff had complained to his psychiatrist that he was falling asleep at day program, typically in the later afternoon and not sleeping through the night, the psychiatrist attributed it to the Alzheimer’s disease and recommended that he get a referral to a neurologist to discuss treatment options. I conveniently saw this patient in the later afternoon, when the symptoms typically arose. I walked in the room, and immediately knew that a sleep study, rather than a neurology referral, was the better initial course of action. He was slumped over in his wheelchair, sound asleep. I had seen this many times before, in particular with patients with Down syndrome. As I suspected, he in fact had severe obstructive sleep apnea, and his symptoms ultimately improved with BiPAP therapy.

Just last week, I met a new patient with autism who came in with recurrent episodes of anorexia. He would refuse to eat or drink, resulting in multiple hospitalizations for dehydration and electrolyte abnormalities. He was notably underweight. I assumed a significant workup had been done, but his parents told me that they had a CT in the ER and were later told no one could find a cause and it was probably his autism. As this was a new problem, and he has had autism his whole life, that assessment was absurd to me. It is obvious that the true underlying diagnosis has been notably delayed.

Diagnostic overshadowing is a common diagnostic error that results from a clinician’s assumption that a given sign or symptom is a direct result of a previously identified diagnosis, when it is in fact due to a separate process. In the case described above, the sleep and behavior changes were incorrectly attributed to a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease when they in fact were due to sleep apnea. Individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities are at particularly high risk for errors due to diagnostic overshadowing, as new symptoms or concerns are all too easily attributed to a patient’s underlying disability, rather than a potential new diagnosis. It is easy to imagine how this would exacerbate the health disparities that this population already faces.

In June 2022, the Joint Commission released a Sentinel Event Alert regarding diagnostic overshadowing in populations facing healthcare disparities. The perils of Diagnostic Overshadowing were brought to the attention of the Joint Commission as a result of a robust and ongoing collaboration with the National Council on Disability (NCD).

At first glance, a newsletter article may seem relatively insignificant, although the potential impact of this alert should not be overlooked. The Joint Commission is a critical body in healthcare regulation and improving patient safety in hospital systems across the United States. They create policies and standards regarding patient safety and formally evaluate hospital systems. It is unprecedented that they would call out a specific issue relating to the healthcare of patients with IDD and other health disparities such as diagnostic overshadowing. It is clearly a step in the right direction, and it is a hopeful sign that policies and procedures could be implemented healthcare system-wide to improve the safety of care provided to individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities.

As clinicians, patients, and family members, we have an opportunity to continue to advocate for policies and standards that further improve safety for patients with IDD, including as it relates to diagnostic overshadowing. The Joint Commission advocates for improved training, improved listening, improved interviewing techniques, improved data collection, using intersectional frameworks in patient care, and improving compliance with the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). Given that the ADA was signed over 30 years ago, and there are still countless hospitals and healthcare practices not meeting accessibility requirements, it is clear that legislation and alerts such as the aforementioned alert are not enough.

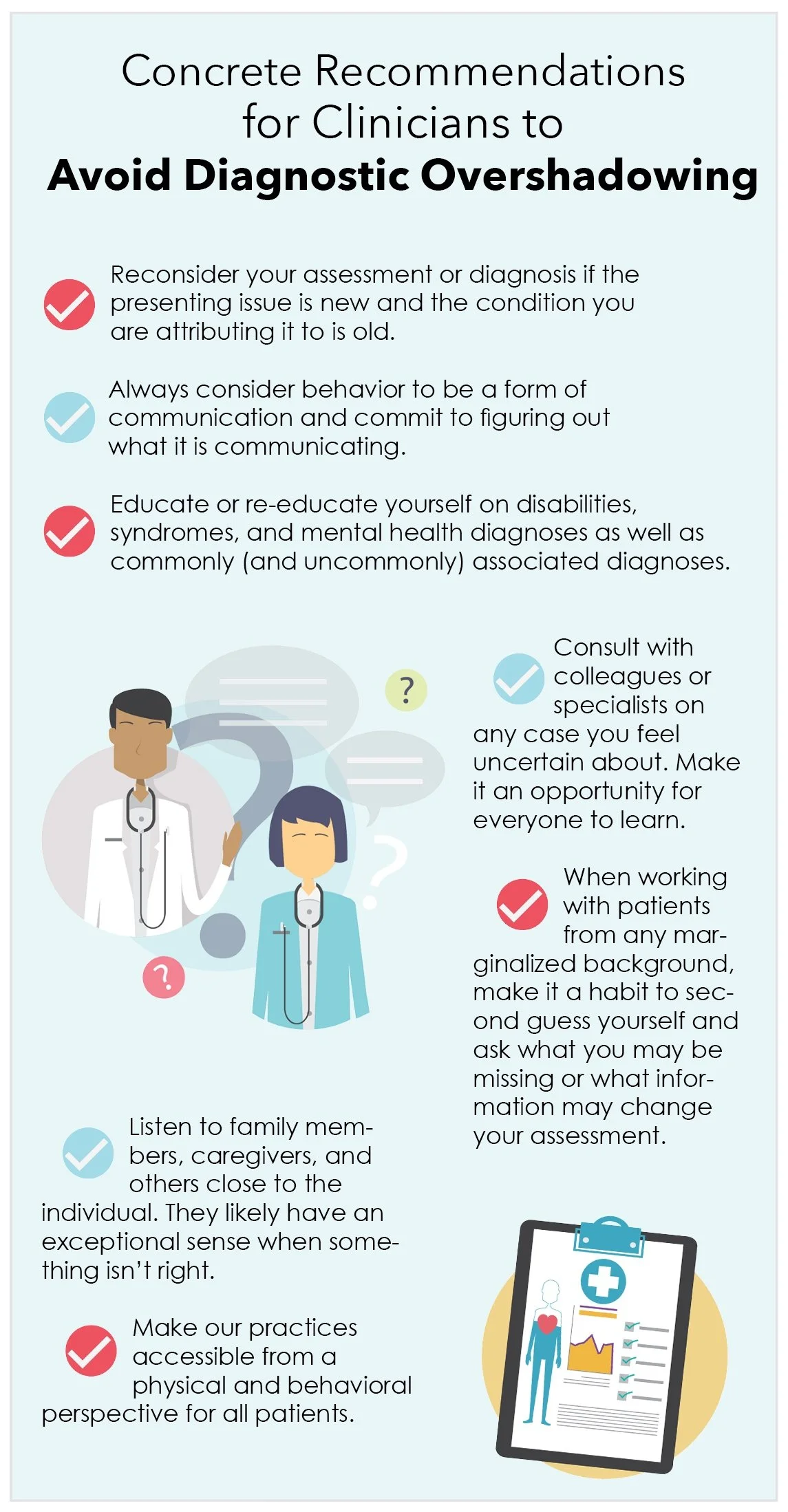

As professionals in IDD care, we have the obligation to run with the framework outlined by the Joint Commission and make it an implemented reality. We must create actionable steps to reduce diagnostic overshadowing as outlined in boxes one and two. We must advocate within our own institutions, but also within the entire healthcare system. We have the opportunity to ensure that these recommendations are made to have a true impact on the quality of care provided to individuals with intellectual disabilities.

About the Author

Emily Johnson, MD is medical director of a primary care clinic for adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities in Colorado Springs, CO and VP Policy and Advocacy of the American Academy of Developmental Medicine and Dentistry. She is also lucky to have both a brother and son who have Down syndrome.