Guiding the Journey: How the Caregiver Support Staging Approach Helps Caregivers of Adults with ID and Dementia Thrive

By Nancy S. Jokinen, MSW, Ph.D.

Dementia changes everything—not just for the person diagnosed, but for those who care for them. For caregivers of adults with intellectual disability (ID), the road to diagnosis and beyond is often unfamiliar and full of challenges. Many find themselves asking: “What is happening to my loved one?” “How can I best support them?” and “Where do I turn next?”

Fortunately, there is a method designed to bring clarity and support to this journey: the caregiver support staging approach, a practical framework adopted by the National Task Group on Intellectual Disabilities and Dementia Practices (the NTG) for use in orientating GUIDE Navigators in assessing caregiver needs of adults with ID and creating meaningful, person-centered dementia care plans.

Whether the caregiver is a devoted parent, an engaged sibling, a professional guardian, or a friend stepping in to help, the Support Staging Model helps answer the most important question: What does this caregiver need right now—and how can we help them prepare for what is next?

Defining the Caregiver Role

Before dementia-related support can be provided, it is essential to understand the type of caregiver involved and their role. Caregivers come from all walks of life and bring different levels of involvement and ability to the role. The caregiver support staging approach can be used by informal and formal helpers to find and better understand caregivers based on the nature of their relationship and responsibilities.

Some are Primary Caregivers, such as aging parents who live with and have supported their adult child for a lifetime. Others are Sibling Caregivers, who may be new to full-time care roles and balancing their own careers and families. Secondary Caregivers are people who live separately from their relative with ID who is affected by dementia yet offer guidance without necessarily daily direct involvement. Still others may be Collaborative Caregivers, sharing responsibilities on a regular basis with either primary or secondary caregivers Others may not fit into any of these categories exactly, which is why the model includes an “Other” option for caregivers with unique or evolving roles.

Accurately understanding the caregiver’s relationship and role allows helpers to match support services to the caregiver’s ability and experience—and ensures that education, communication, and planning are aligned with real-world conditions.

-—

JEAN and JOHN

Jean M., an accountant, has recently taken on the role of primary caregiver for her older brother, John, a man in his 60s with an intellectual disability. Until recently, John lived in an apartment with two housemates, supported by a local disability agency. However, as John began to show increasing forgetfulness and declining ability to manage daily life independently, he moved in with Jean. Over the past several months, Jean has observed further changes in John’s behavior and ability to participate in household routines. Concerned, she consulted their family doctor, who referred John for a memory assessment. The memory clinic concluded that John is likely in the early stage of dementia. While Jean is committed to providing care, she recognizes that her responsibilities are growing. She has begun to explore caregiving resources but is seeking more information about the progression of dementia and the adjustments she will need to make. Even though she works from home, Jean is becoming increasingly concerned about how to balance her professional duties with her caregiving role.

Questions that might be asked of Jean:

Ꙩ What specific daily activities or household tasks does John need help with now, and how has this changed from six months ago?

Ꙩ What formal or informal supports (family, friends, community services) are currently available, and how consistently can they assist?

Ꙩ How knowledgeable does she feel about dementia progression and strategies for supporting a person with both intellectual disability and dementia?

Likely caregiver support stage:

Based on the scenario, Jean is a sibling caregiver likely in the "Exploratory Stage" — she has just received a diagnosis, is seeking information, and is beginning to navigate what supports will be needed in the future, but her caregiving role is still emerging. Her key needs appear focused on further education, planning, and resources to help her manage the situation.

-—

Understanding the Four Phases of Caregiving

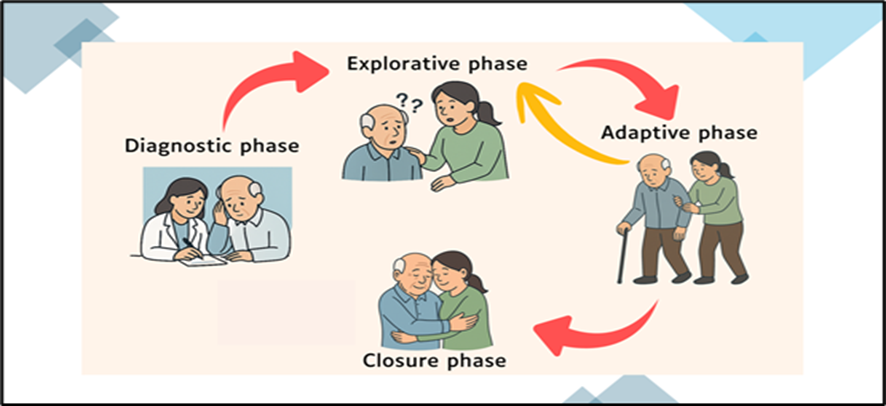

The caregiver support staging approach is built on a clear recognition: caregiving is not static. It changes as dementia progresses, and so do the caregiver’s needs. The model outlines four phases of the caregiving experience—Diagnostic, Explorative, Adaptive, and Closure—each defined by distinct patterns of need, emotion, and action, but also at times are overlapping. The Support-stage process is illustrated in the graphic.

By mapping where a caregiver is along this continuum, helpers can become better acquainted with the caregiver and personalize support and avoid a “one-size-fits-all” approach. It can serve as the starting point for a conversation around what caregiving means and the impact when dementia is present.

Phase 1: The Diagnostic Phase

Key Need: Recognition, Reassurance, and Diagnostic Support

Caregivers in the diagnostic phase may be just beginning to notice changes, such as confusion, altered routines, unusual behaviors. They may suspect cognitive changes or dementia but are unsure how to interpret what they are seeing—or what to do about it. Often, caregivers have not yet pursued a formal evaluation, or they are waiting for confirmation. Yet, as dementia progresses, other changes also occur that are concerning to caregivers. There’s uncertainty, hesitation, and a need for guidance.

What help can be provided? Information on the early signs and progression of dementia in adults with ID. Help with prompt assessments and support during the diagnostic process. Offering emotional reassurance and confirm concerns.

Phase 2: The Explorative Phase

Key Need: Education, Planning, and Resources

Once a diagnosis is confirmed, caregivers begin seeking answers—about progression, available services, and what the future may hold. They may express worry about coping with changes, medical needs, finances or the future but lack concrete plans. This is a critical period for laying the groundwork for managing daily care as well as planning long-term care.

What help can be provided? Information on brain disease progression and associated health concerns. Exploring support options to address immediate concerns including home modifications, safety strategies, and respite. Introductions to available support networks, services, and advocacy tools. Aid with care planning for emergency situations and the future.

Phase 3: The Adaptive Phase

Key Need: Practical Strategies, Behavioral Management, and Emotional Support

In the adaptive phase, caregivers are fully immersed in the demands of daily dementia care. The caregiver is adjusting routines and trying new approaches to address functional and behavioral changes of concern. The caregiver may at times feel overwhelmed, exhausted, and in need of planned help.

What help can be provided? Provide encouragement, ongoing support, and training to manage cognitive and behavioral symptoms. Complete needed home modifications and implement safety strategies. Encourage self-care strategies to reduce caregiver stress, including possible use of respite care and participation in support groups.

Phase 4: The Closure Phase

Key Need: Transitions, End-of-Life Planning, and Post-Caregiving Support

In this final stage of the caregiver support staging approach, caregivers may have resolved initial concerns providing care with changes they made in their care routines, or in using strategies that have had a positive impact on quality of life and daily life care. Their first priorities have been addressed.

However, many caregivers will have ongoing needs confronting more and advanced dementia symptoms and the toll of anticipatory grief. Other caregivers may be exiting their caregiving role after a loved one’s death, needing space to grieve and reflect on their experiences.

What help can be provided? Ongoing support for caregiver concerns that arise over the course of dementia. Check ins to watch for caregiver stress. Seeking out palliative or hospice care as needed. Getting guidance on legal and emotional aspects of end-of-life plans. Grief counseling and connection to post-caregiving supports.

Creating Person-Centered Dementia Care Plans

One of the greatest strengths of the caregiver support staging approach is its ability to inform action. The NTG believes that by better understanding both the caregiver’s role and phase of engagement, helpers can build a customized, formal, or informal person-centered care plan that is responsive to both the needs of the adult with ID and the caregiver providing support.To aid this process, a guide and useful form was created to better understand the caregiver support staging approach and identify the needs to help sustain a caregiver in their dementia care journey.

“DR. JOKINEN ACKNOWLEDGES THAT, ‘KNOWING AND UNDERSTANDING WHERE THE CAREGIVER IS IN THEIR DEMENTIA CAREGIVING JOURNEY CAN HELP SHAPE WHAT ASSISTANCE MAY BE MORE USEFUL AT ANY POINT IN TIME.’”

The NTG has also paired this approach with the use of the Gerontological Society of America’s (GSA) Addressing Brain Health in Adults with Intellectual Disabilities and Developmental Disabilities: A Companion to the GSA KAER Toolkit for Brain Health (KAER ID/D). This kit, an adaptation of the GSA’s KAER framework, helps with dementia screening, diagnosis, and care planning for individuals with ID and other developmental disabilities.

One application of the caregiver staging support approach and the GSA’s toolkit has been the NTG’s Changing Thinking! project which has been designed to aid the CMS’s GUIDE Model navigators. Here, the NTG created specialized training materials and technical help resources to enhance the navigators’ capabilities to assess and enroll more beneficiaries with ID. The training models developed cover three core areas: (1) information on ID and dementia care planning, (2) aiding caregivers of persons with ID, and (3) resourcing dementia services. The GSA KAER-ID kit and the caregiver support staging approach are important parts of this effort to aid caregivers.

Helpers may come from the community’s providers of services, as well as friends and neighbors who look after a person with dementia. Formal dementia providers can use the model to create sound dementia care plans that would include:

Training modules tailored to caregiver experience and capacity

Recommendations for community services, therapies, or adaptive equipment

Emergency and respite planning

Communication strategies and routines adapted for dementia

Housing transitions and long-term care options

Grief and transition supports, post-caregiving

Informal helpers can use the approach to appreciate what the caregiver is experiencing, perceiving, and may be most in need of. Help might center around:

· Helping with respite – or time off from the daily demands of caregiving

· Aiding with sorting out who or what organizations might be most helpful

· Being a ‘receptive ear’ to listen to the caregiver and discuss helping options

· Taking some time to spend with the adult with dementia

Whether formal or informal, dementia care plans need to reflect a core principle: Care must be dynamic, individualized, and attuned to the relationship between caregiver and the adult affected by dementia.

Conclusion: Meeting the Moment with Support and Structure

Dementia is a complex, progressive condition that changes lives—yet with the right framework, caregivers of adults with intellectual disability do not have to face it alone or unprepared. The NTG firmly believes that the caregiver support stage approach can give helpers the structure they need to deliver ongoing tailored support, identify challenges, and ensure that caregivers receive what they need when they need it most.

At its heart, the model affirms a simple but powerful truth: caregiving is a journey. It deserves attention, respect, and above all, responsive support that meets caregivers where they are—and walks with them every step of the way.

Interested in learning more about the NTG’s Changing Thinking! Project and how the caregiver support staging approach is used in agency caregiver aid programs? Visit www.the-ntg.org/changingthinking for tools, training, and caregiver resources.

About the Author

Dr. Nancy S. Jokinen, MSW, PhD, is Vice President of the National Task Group on Intellectual Disabilities & Dementia Practices (NTG) and holds an adjunct professorship at the University of Northern British Columbia’s School of Social Work. In collaboration with Canadian colleagues, she co-leads the NTG–Canadian Consortium on Intellectual Disabilities and Dementia, where she and colleagues adapted the NTG Education & Training Curriculum for Canadian practice, and actively develops and delivers training to support families and individuals with intellectual disabilities affected by dementia. As lead author of the Caregiver Support Staging approach, published in the Journal of Gerontological Social Work, she coordinated an international team to conceptualize and describe progressive caregiving support stages tailored to people aging with intellectual disability and dementia, and has led its integration into NTG’s GUIDE Navigator learning management system.