Exercise as Medicine Across the Autism Spectrum

A Conceptualized Framework

David S. Geslak, BS, ACSM-EP, CSCS, Robyn T. Boudreaux and Benjamin D. Boudreaux, PhD3

Abstract

The prevalence of autism spectrum disorder is 1 in 31 children in the United States and is associated with increased risk for obesity, diabetes, hypertension, and shorter life expectancy. While the benefits of exercise for individuals with autism spectrum disorder are shown to be beneficial, federal endorsed guidelines and exercise prescriptions such as the FITT principle (Frequency, Intensity, Time, Type) fail to account for the complexity and diversity of the autistic population. The present article addresses the applicability of traditional exercise prescriptions for autistic individuals and presents a new conceptualized personal recommendation based on current data available, lived experiences, and evidence-based teaching strategies.

Introduction

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is one of the five most prevalent intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDDs) over the past two decades, with rates increasing from 1 in 150 children in 2000 to 1 in 31 today (1). The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition, provides a specifier for physicians to determine three different severity levels of autism based on their support needs: level 1 (“requiring support”), level 2 (“requiring substantial support”), and level 3 (“requiring very substantial support”) (2). Compared to their neurotypical peers, autistic individuals face increased health risks of developing long-term health conditions (i.e., obesity, hypertension, diabetes, sleep difficulties, etc.) at an earlier age, resulting in a shorter life expectancy due to inadequate physical activity (3,4).

Despite the health benefits of physical activity for individuals with ASD, many face multiple barriers to being or staying physically active (5–7). The path from inadequate levels of physical activity to meeting the physical activity recommendations is obstructed not by lack of willingness but by the complexity of autism itself. Autism has wide-ranging characteristics in communication, motor coordination, and sensory processing that make the introduction of exercise challenging (2,8–10). For example, getting up and down from the ground, catching a ball, or sitting/standing in an upright posture may be easy for one person but difficult for another person. Federally endorsed guidelines (i.e., 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans, World Health Organization) recommend children with disabilities engage at least 60 min·d−1 of moderate to vigorous physical activity daily and adults living with a disability engage at least 150 to 300 min·wk−1 of moderate-intensity, 75 to 150 min·wk−1 of vigorous physical activity, or an equivalent combination of both (11,12). Individuals also should perform muscle strength training on all major muscle groups two or more days per week (11,12). Despite scientific advancements, the standard approach of informing appropriate levels of physical activity and exercise in this population remains largely unchanged (13).

The FITT principle (Frequency, Intensity, Time, and Type) is a foundational model in exercise science and prescription that offers a structured framework for guiding exercise programming, often prioritizing aerobic activity as the entry point (14). Although this model is useful for the general population, it is not designed for autistic individuals or individuals with IDDs. It does not account for the need for structure without rigidity, intensity without overwhelming the individual, or time frames that reflect attention spans and regulation needs. It also overlooks the critical role of predictability, proprioception, and personal interest — factors that are critical toward exercise engagement and success including for those with ASD (8,10). Thus, initiating exercise or promoting optimal levels of physical activity in this population requires a comprehensive understanding of the individual's severity of autism, environment, physiological responses, and personal interests.

To develop an appropriate FITT framework for individuals with ASD, it is essential to evaluate scientific data alongside the lived experiences of individuals with autism and their caregivers (10,15–17). This paper addresses these factors by providing voices of a caregiver, autistic individual, and practitioner. We also propose a recommended FITT principle stratified by autism severity based on current scientific evidence. Finally, we provide a step-by-step process in order to effectively start an exercise program for those with ASD.

The Human Perspective: What Lived Experience Tells Us

Autistic individuals, their caregivers, and practitioners offer distinct themes that are in research studies (18–20). Their voices reveal the nuance behind what it means to introduce, sustain, succeed, and/or struggle with exercise in everyday life. Their voices are not simply personal accounts or anecdotal but inform important considerations of how to educate others, design programs, and define success.

Caregiver Perspective (Robyn T. Boudreaux)

We expect our children to surpass us academically, socially, even athletically. But when your child has autism, the path is rarely linear. In third grade, Ben was labeled disruptive and did not connect well with peers or teachers. By seventh grade, he finally learned to ride a bike. I assumed he was not interested in sports because of his motor skill difficulties and bullying. He spent most of his time playing video games, eating poorly, and avoiding movement.

In third grade, his teacher recommended a psychological evaluation, which led to diagnoses of learning variability, dyslexia, and anxiety. In eighth grade, after severe bullying and emotional withdrawal, a second evaluation confirmed an autism diagnosis.

High school brought more challenges. Ben lacked the motor skills to join teams. His posture soon declined, and depression developed. I overheard one parent call him “the kid with the hunchback.” His doctor recommended physical therapy (PT), but as a single working parent with limited insurance coverage, it was unrealistic. He was prescribed an antidepressant, which helped a bit, but I knew he needed more.

I turned to exercise — the one thing I knew. I am a runner, but I started small with Ben. I brought him to the gym just to observe. At home, we took “outings” — 2-hr walks to a pond where we fed ducks. During the walks, I asked him to come jog. He got 20 to 30 mins of jogging during each outing, which was two times per week.

I was proud of his progress in high school, but his transition to college brought new challenges. When Ben came home after one semester, I introduced him to weight machines at the same gym he observed during high school. To cope with his depression and improve his posture, I had him lift weights focusing on his shoulders, back, and chest. I kept it simple. He did three machines with three sets of 10 repetitions each. He tried and that was all I wanted. This routine gave him structure, confidence, and a sense of progress that felt manageable. Exercise had to be individualized for Ben to succeed. If I had focused on national standards, we both would have felt like failures. Families already manage so much—therapy, education, daily routines.

What changed things for Ben was not intensity or duration — it was routine, consistency, and the growing belief that he could do it. Once he found comfort in his own rhythm, there was no limit to what he could achieve.

His story is a powerful reminder of what becomes possible when we meet autistic individuals where they are—nowhere guidelines say they should be.

The Lived Experience (Benjamin D. Boudreaux)

As someone with autism and type 1 diabetes, I have done things others often label as “inspirational”—running two World Marathons. Majors, earning a PhD, and a postdoctoral fellow. I have simply set goals, stayed focused, and sought support — just like anyone else.

In eighth grade, I barely could catch a ball or enjoy physical education (PE). While my PE teachers may have known about my poor motor skills, they did not know how to help. This lack of awareness led to frequent bullying by my peers—leading to anxiety, depression, and lack of physical activity interest.

As a child and teenager, I remember my mom bringing me to the gym—not to work out, but just to watch. I always thought, “Why am I here? This is a waste of time!” I did not see anyone my age. Little did I know how much that experience would change my life.

During the outings to feed the ducks, I actually did not remember running until I read my mom’s narrative. My sole reason to get out of the house to walk, and run, was to just feed the ducks — my reinforcement (21).

In college, due to my poor performance as an athletic training student, I share my autism diagnosis with the department head. He dismissed me and said, “I don't know what autism or how to accommodate you so maybe this isn't the right program for you.” That shattered me and sent me into a deep depression.

To overcome this state, my mother suggested that I try using the weight machines and walking on the treadmill or cycling. I realized it was not exercise I hated—it was the group dynamics of PE: the noise, pressure, and lack of instruction. When I was able to move at my own pace, everything changed. Lifting weights became a turning point. My anxiety decreased, my focus improved, and the weight on my mind felt lighter. I learned that cardio lifted a mental “fog” and made me less irritable. To this day, I start with the bike or elliptical, then lift. As my exercise volume increased over the years, I unexpectedly encountered a new hurdle.

In 2020, I developed symptoms of hypoglycemia, polyuria, polydipsia, and feelings of fatigue daily especially during exercise. After multiple tests, I was diagnosed with type 1 diabetes. While diabetes brought new challenges to my daily routine, I did not stop exercising but instead took it a step further beginning in 2022.

As such, I ran the NYC Marathon in 2023 in 3:28, which soon qualified me to run and finish the 2025 Boston Marathon in 3:48.

There is no cure for autism or diabetes, but exercise gives me control. I do not follow the guidelines—I follow what works. What began with hesitation became healing. Not through intensity or time, but through support, trust, and the freedom to begin slowly.

Practitioner Perspective (David S. Geslak)

In 2004, a father asked me to help his autistic son learn to skip—something they had been working on for years. I barely understood autism because it was not covered in my undergraduate degree or certifications. But I was determined to help. I broke down the skipping pattern into small steps just as I learned when reteaching Olympic lifts to freshman football players at the University of Iowa. After four sessions, the child was skipping. His mom cried, his dad was speechless, and his smile said everything. That moment sparked an exercise career dedicated to support individuals with autism and their families.

I have worked with thousands of autistic individuals in homes, schools, and gyms. The first priority is not cardiovascular endurance — it is building trust and a positive connection with exercise. Progress toward a movement goal can be life changing —not just physically, but emotionally.

Early in my career, I read a study about those with autism that stated, “a physical activity-based program is easy to implement …” (22). In practice, especially using FITT, they were not easy. Motor, sensory, and cognitive differences pose challenges especially for the ASD severity levels.

While applying evidence-based teaching practices, I gradually introduce strength, flexibility, core stability, and motor coordination exercises. These foundational elements helped many transitions into aerobic activity.

I conducted most 1:1 sessions once a week for 60 min, but because individuals often required sensory breaks, the time spent actively exercising was usually between 25 and 35 min. In my group classes at a therapeutic day school for children with autism, I created stations to differentiate instruction (23).

The initial objective was not exercise; it was to help the group become accustomed to a consistent routine. It became clear: knowing what to teach is not enough, you must know how the individuals learn best. A study showed that after completing the Autism Exercise Specialist Certificate Course, professionals' self-efficacy and frequency of use in applying evidence-based strategies when working with those with ASD significantly increased (24). Evidence-based practices are critical to the success of any ASD exercise program (21). Even a single visual can open a door to connection. When individuals with ASD are met with compassion and clarity — like Ben was—they do not just participate, they progress. That is why this framework matters. With the proper tools, education, and individualization, we can end the cycle of missed opportunities and build a path to lasting engagement and success.

FITT Is Not the Right Fit for ASD

The FITT principle was introduced in 1975 and remains the foundation of exercise programming for most populations (14). The FITT Guidelines for Aerobic Exercise Recommendations are as follows: frequency at least 3 daily and adults and every day for children; intensity of moderate and/or vigorous for adults and children; for time, adults should accumulate 30 to 60 min·d−1 of moderate intensity, 20 to 60 min of vigorous intensity or a combination of both; children should accumulate 60 min of moderate to vigorous daily, and type aerobic performed in a continuous or intermittent manner (14).

To date, no specific FITT recommendation has been devised for individuals with ASD for a variety of reasons: 1) Nearly all federally funded National Institutes of Health (NIH) population-based studies and national surveillance systems include participants documented with autism or an IDD, 2) 75% of NIH funded clinical trials directly or indirectly excluded adults with IDD(25), 3) only 2 of 11 randomized clinical trials were statistically powered enough to examine beneficial weight loss in adolescents (primarily Down syndrome (DS)) (26), 4) numerous studies are limited to associations between physical activity behavior and a health outcome rather than explore dose-response relationships (27), and 5) exercise interventions utilize various different modalities (14). These scientific limitations continue to create gaps in the development of a FITT principle recommendation and need to be addressed. ACSM's Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription recommends that “people with ASD are prescribed exercise to gradually progress to a frequency, intensity, and time that is recommended for people without ASD” (14). These recommendations do not account for ASD severity, which precludes individualized prescriptions. The benefits of having an individualized FITT recommendation by ASD severity may inform greater potential for healthcare providers, educators, and the fitness industry to increase physical activity in this population.

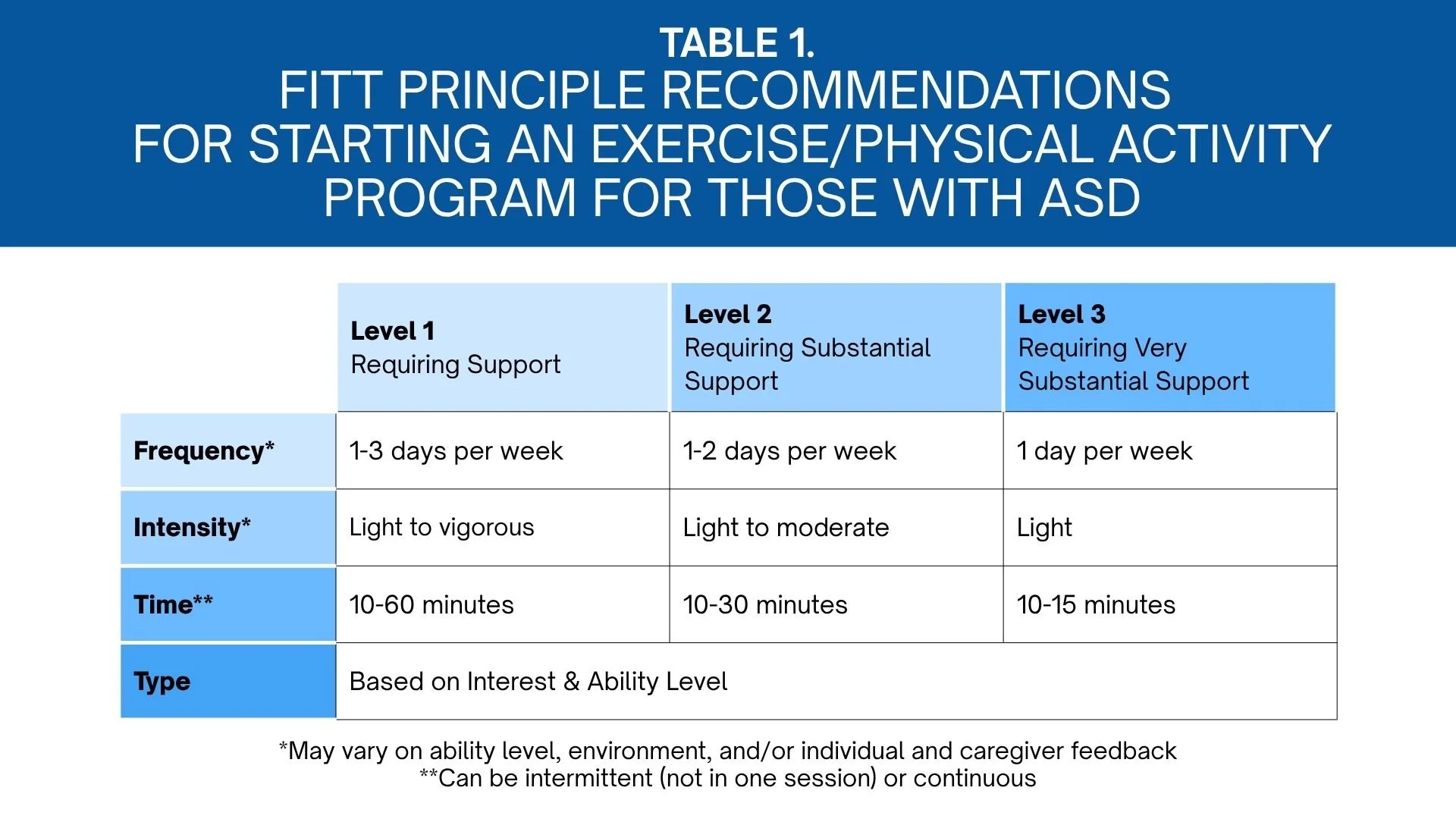

The Table outlines the FITT principle recommendation stratified by ASD to effectively start an exercise program.

Frequency

Regular exercise engagement is often unpredictable for a variety of reasons in an autistic individual. When a child is diagnosed, individuals and their caregivers are entrenched in early intervention, which includes some or all of the following services: developmental therapy, PT, occupational therapy, and/or speech-language pathology (28–30) services; developmental therapy (e.g., applied behavior analysis) alone can be prescribed for up to 36 h·wk−1 (31). The importance of these therapies play a crucial role in helping individuals regulate their bodies, communicate effectively, and develop both daily living and gross motor skills. Beyond these therapies, many caregivers believe their children are meeting appropriate levels of physical activity during adapted PE (APE) or PE. However, educators reported being ill-equipped to teach students with ASD, and autistic students reported having negative experiences in PE (24). Thus, PE and APE do not provide an accommodating atmosphere to be physically active in order to improve their academics, on-task behavior, and language development (21).

Asking individuals and caregivers to meet physical activity recommendations and add three to seven exercise sessions per week to their child's schedule is unrealistic. As provided in the Table, individuals with autism should exercise for a minimum of 1 d·wk−1. Individuals with a lesser severity (level1) should engage 1 to 3 d·wk−1, on consecutive or nonconsecutive days, depending on the individual's interest and ability. Individuals with a level 2 classification should engage for at least 1 to 2 d·wk−1, and those at a level 3 classification should attempt for at least 1 d·wk−1. Table.

FITT principle recommendations for starting an exercise/physical activity program for those with ASD.

Intensity

Emerging evidence has demonstrated that autistic individuals display distinct differences in motor behavior compared to their neurotypical peers (32). These differences fall into two main categories: motor stereotypies — such as hand flapping, rocking, or spinning — and motor coordination challenges, which can include postural instability, balance impairments, hand–eye coordination difficulties, and inefficient movement patterns. These challenges make engaging in moderate- to vigorous-intensity exercise — often characterized by continuous, rhythmic movement and high coordination demands — difficult for those with ASD.

A systematic review examining the effects of aerobic intensity on stereotypic behaviors in individuals with ASD concluded that 10 to 15 min of light- to moderate-intensity aerobic exercise was effective in decreasing stereotypic behaviors, with effects lasting between 30 and 120min (33). This suggests that meaningful outcomes do not require high levels of exertion, and in many cases, lower-intensity movement may be both more accessible and more beneficial. However, measuring exercise or physical activity intensity also may be a challenge for those with ASD.

Borg's Rating of Perceived Exertion is a valuable indicator to monitor a person's perceived effort during an activity (14). According to ACSM's Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription, an individual's perception of exercise can be influenced by a multitude of factors, such as personal health and exercise history, demographics, and testing environment (14).

However, this assessment does not take into consideration the expressive and receptive language of autistic individuals. Pictures or visuals are a significant means of communication for those with autism (21). As such, one study examined the validity of a pictorial perceived exertion scale (PCERT) on typically developing middle school children and found that PCERT was accurate in matching perceived exertion with actual exertion levels (34).

We recommend the integration of pictorial exertion scales in both testing and prescription, as they align with how many autistic individuals process and communicate information, and offer a more inclusive method for assessing intensity.

Additionally, DS is a co-occurring condition with autism. When measuring aerobic capacity in both children and adults with DS, research has shown the presence of chronotropic incompetence — defined as the inability of the heart rate to increase appropriately during exercise to meet the body's physiological demands (35–38). This blunted heart rate response can significantly affect how exercise intensity is perceived and measured.

Considering autism severity levels, it stands to reason that exercise intensity guidelines also must be individualized. Rather than aiming for traditional heart rate zones or assumed thresholds of exertion, practitioners should focus on creating opportunities for movement that are repeatable and self-regulating.

The Table outlines the intensity recommendations among those with autism based on their severity level. All autistic individuals should initially begin exercise at a light intensity but should progress at higher intensities based on their severity level (level 1: light to vigorous, level 2: light to moderate, level 3: light) when responses to exercise are appropriate.

Time

Aerobic guidelines recommend adults with disabilities engage in at least 150 to 300 min·wk−1 of moderate-intensity physical activity, or 75 to 150 min·wk−1 of vigorous intensity per week or an equivalent of both, and children engage in 60 min of moderate to vigorous physical activity daily (12). Emerging evidence suggests 10 to 15 min of exercise provides initial health benefits in autistic individuals and should be considered a realistic introduction to exercise (33). A starting goal of 10 to15minis realistic and achievable, not only for the individual but also for caregivers, exercise professionals, and/or PE/APE teachers (33).

The Table provides the time recommendations for those with ASD by their severity level classification. Minimum of10 min·d−1 should be emphasized across all levels, and gradual progression of time should be applied to those needing less support (level 1), while those needing additional support (levels 2 and 3) will progress at their own pace whether it be a child or an adult.

Type

Aerobic activity is positioned as the cornerstone of public health exercise recommendations due to its well-documented benefits of reducing the risk of chronic conditions and shorter mortality (39). While the World Health Organization, ACSM, and the 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans offer well-intentioned guidance for physical activity, their emphasis on cardiovascular endurance has been broadly applied across all populations, including individuals with disabilities—often without regard for foundational motor challenges (11,12). Aerobic exercise may seem simple, but it relies on a collaboration of systems working in balance. Cardiorespiratory endurance, defined as the ability of the circulatory and respiratory systems to supply oxygen during sustained physical activity (14), requires more than biological function. It requires the ability to move the body rhythmically and continuously, often for extended periods of time. To do so, the body requires muscular strength, muscular endurance, and flexibility. In addition, it requires the skill-related physical fitness components balance, coordination, and agility (14). As outlined in the intensity section, motor challenges in autistic individuals often begin in early childhood and continue well into adulthood.

Difficulties with crawling, walking, balance, and coordination are not just developmental delays that fade with time — they can be lasting features. These movement-related differences, such as instability during movement or inefficient motor control, can make it especially difficult to start or maintain rhythmic, sustained activities like aerobic exercise (32). The assumption that aerobic activity is the entry point to exercise for autistic individuals is deeply problematic.

A systematic review by Ataíde et al. (2024) concluded that individuals with IDD who combined both cardiorespiratory fitness and muscular strength effectively improve their cardiovascular capacity and hemodynamic parameters (40). For children and adults with ASD, we should consider introducing exercise through all components of health- and skill-related physical fitness. Although further research is needed in this area, exercises that focus on muscular strength, muscular endurance, and flexibility may offer a more accessible starting point and improve outcomes (41,42). As provided in the Table, the type of physical activity and exercise should be based on the autistic individual's interest and ability level.

The Right Delivery: A Framework That Centers the

Autistic Individual

Traditional conceptualized frameworks are developed and presented as a visual to standardize an approach as an idea, thought, or concept with physical activity (43). Theoretical frameworks may not be reflective for the ASD population as multiple domains and abstract constructs may influence the individual's physical activity or exercise adherence (44). Westrop et al. (2024) conducted a realist evidence synthesis that combined systematic review methods with cocreation methods wherein IDD individuals with lived experience were heavily involved to develop a framework for lifestyle interventions (44). Individuals in key support roles, particularly caregivers and direct support professionals, play a significant role in influencing lifestyle modification in this population. Thus, it is imperative to create and standardize a stepwise framework that can be generalizable across healthcare professionals, educators, and caregivers who execute an exercise assessment, prescription, and evaluation in order to promote successful engagement and retention in ASD.

The Figure provides a conceptualized step-by-step process of how to effectively assess an autistic individual, build an exercise program, and progress their adherence to achieve recommended guidelines and make exercise and physical activity part of their lifestyle. The initial step should be to understand the autistic individual's physical activity interests (running, walking, biking, swimming, etc.) and abilities with the use of established evidence-based practices (visual supports, video modeling) from the individual, caregiver, and/or healthcare provider. Second, an examination of the individual's overall health (if any chronic conditions are present) and fitness level should be performed to curate an effective exercise prescription. Once an exercise prescription is devised, the professional can execute the exercise session while continuously evaluating the individual's response toward the physical activity modality, frequency, intensity, and the length of exercise. To ensure positive responses and a consistent routine, the professional may need to revise an exercise prescription if an autistic individual is not interested or able to perform a specific activity.

Due to certain environmental sensitivities (e.g., brightness, noise) or unknown factors, modifications to the exercise prescription or environment may be needed by the individual, caregiver, healthcare provider, or exercise professional.

Finally, professionals should consistently ask for feedback from the individual or caregiver to determine if modification is necessary.

Conclusion

Despite the benefits of exercise, autistic individuals remain among the least physically active due to misaligned approaches and inaccessible implementation models. Traditional standards, like the FITT principle, fail to account for neurodevelopmental, motor, and sensory differences across the autism spectrum. This paper offers insights from a caregiver, autistic adult, and practitioner to reveal the gap between generalized guidelines and individual needs.

We propose an individualized framework stratified by autism severity and share a step-by-step process to assess, prescribe, and adapt sport/exercise programs. To advance the field, we call for three key actions: 1) examine long-term associations of physical activity and health in autistic individuals through population-based studies; 2) examine dose-response effects of physical activity and health outcomes in different populations of IDD; and 3) implement autism-specific, evidence-based exercise training across professional settings.

This shift is essential to foster lasting participation and improve health outcomes for autistic individuals.

Disclaimer: We use identity-first and person-first language as we discuss the autistic community or persons with autism. Current best-practice recommendations encourage avoidance of disorder-focused or medicalized language in discourse, but we want to respect the preferences of the entire autism/autistic community. This manuscript also was written by someone who identifies as a person with autism. Personal narratives in this article may not fully represent the experiences of all individuals with autism. It also is important to recognize that while many individuals with autism may rely on a parent or caregiver, not all individuals remain dependent on one throughout their lives.

Conflict of interest: There are no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding/support: No external funding was provided for this study.

Preprint server disclosure: Preprint server was not used.

References

1. Shaw KA, Williams S, Patrick ME, et al. Prevalence and early identification of autism spectrum disorder among children aged 4 and 8 years — autism and developmental disabilities monitoring network, 16 sites, United States, 2022. MMWR Surveill. Summ. 2025; 74:1–22.

2. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and StatisticalManual of Mental Disorders. DSM-5, text rev ed. Arlington (VA): American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2022.

3. Diaz KM. Leisure-time physical activity and all-cause mortality among adults with intellectual disability: the National Health Interview Survey. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2020; 64:180–4.

4. O'Leary L, Cooper SA, Hughes-McCormack L. Early death and causes of death of people with intellectual disabilities: a systematic review. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 2018; 31:325–42.

5. Lang R, Koegel LK, Ashbaugh K, et al. Physical exercise, and individuals with autism spectrum disorders: a systematic review. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 2010; 4:565–76.

6. Ruggeri A, Dancel A, Johnson R, Sargent B. The effect of motor and physical activity intervention on motor outcomes of children with autism spectrum disorder: a systematic review. Autism. 2020; 24:544–68.

7. Sowa M, Meulenbroek R. Effects of physical exercise on autism spectrum disorders: a meta-analysis. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 2012; 6:46–57.

8. Geslak DS, Boudreaux BD. Exercise is a life-changer for those with autism. ACSMs Health Fit. J. 2021; 25:12–9.

9. Yanardağ M, Aras İY, Özgen Aras Ö. Approaches to the teaching exercise and sports for the children with autism. Int. J. Early Child. Spec. Educ. 2010; 2:214–30.

10. Geslak DS. Exercise, autism, and new possibilities. Palaestra. 2016; 30.

11. Bull FC, Al-Ansari SS, Biddle S, et al. World Health Organization 2020 guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour.Br. J. SportsMed. 2020; 54:1451–62.

12. Piercy KL, Troiano RP, Ballard RM, et al. The physical activity guidelines for Americans. JAMA. 2018; 320:2020–8.

13. BurnetK,Kelsch E,Zieff G, et al.Howfitting is F.I.T.T.?A perspective on a transition from the sole use of frequency, intensity, time, and type in exercise prescription. Physiol. Behav. 2019; 199:33–4.

14. Ozemek C, American College of Sports Medicine. ACSM's Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription. 12th ed. Philadelphia (PA):Wolters Kluwer; 2025.

15. Chown N. Improving research about us,with us: a draft framework for inclusive autism research [the version of record of this manuscript was published on 05 May 2017 and is available in disability and society at http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/09687599.2017.1320273]. Disabil. Soc. 2017; 32:720–34.

16. Fletcher-Watson S, Adams J, Brook K, et al.Making the future together: shaping autism research through meaningful participation. Autism. 2019; 23:943–53.

17. Pickard H, Pellicano E, den Houting J, Crane L. Participatory autism research: early career and established researchers' views and experiences. Autism. 2022; 26:75–87.

18. Arnell S, Jerlinder K, Lundqvist LO. Parents' perceptions and concerns about physical activity participation among adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. Autism. 2020; 24:2243–55.

19. Beattie C, Streetman AE, Heinrich KM. Empowering personal trainers to work with individuals with disabilities to improve their fitness. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2024; 21:999.

20. Geslak D. The Autism Fitness Handbook: An Exercise Program to Boost Body Image,Motor Skills, Posture and Confidence in Children and Teens with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Philadelphia (PA): Jessica Kingsley Publishers; 2014.

21. HumeK, Steinbrenner JR, OdomSL, et al. Evidence-based practices for children, youth, and young adults with autism: third generation review. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2021; 51:4013–32.

22. O'Connor J, French R,Henderson H. Use of physical activity to improve behavior of children with autism— two for one benefits. Palaestra. 2000; 16:22–29.

23. Schultheis SF, Boswell BB, Decker J. Successful physical activity programming for students with autism. Focus Autism Other Dev. Disabil. 2000; 15:159–62.

24. McNamara SWT, SeanH,Melissa B, Blagrave J. Physical educators' experiences and perceptions towards teaching autistic children: a mixed methods approach. Sport Educ. Soc. 2023; 28:522–35.

25. McDonald KE, Schwartz AE, Sabatello M. Eligibility criteria in NIH-funded clinical trials: can adults with intellectual disability get in? Disabil. Health J. 2022; 15:101368.

26. Hilgenkamp TIM,Davidson E,Diaz KM, et al.Weight-loss interventions for adolescents with Down syndrome: a systematic review. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2025; 33:632–58.

27. Pitchford EA, Dixon-Ibarra A, Hauck JL. Physical activity research in intellectual disability: a scoping review using the behavioral epidemiological framework. Am. J. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2018; 123:140–63.

28. Corsello CM. Early intervention in autism. Infants Young Child. 2005; 18:74–85.

29. Matson JL, Konst MJ. Early intervention for autism: who provides treatment and in what settings. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 2014; 8:1585–90.

30. Vivanti G, Kasari C, Green J, et al. Implementing and evaluating early intervention for children with autism: where are the gaps and what should we do? Autism Res. 2018; 11:16–23.

31. Linstead E,DixonDR,Hong E, et al. An evaluation of the effects of intensity and duration on outcomes across treatment domains for children with autism spectrum disorder. Transl. Psychiatry. 2017; 7:e1234.

32. MillerHL, LicariMK, BhatA, et al.Motor problems in autism: co-occurrence or feature? Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2024; 66:16–22.

33. Rodriguez-de-Dios V. Effects of light to moderate intensity aerobic exercise on stereotypic behaviours in subjects with autism spectrum disorder: a systematic review. Palaestra. 2023; 37.

34. Yelling M, Lamb KL, Swaine IL. Validity of a pictorial perceived exertion scale for effort estimation and effort production during stepping exercise in adolescent children. Eur. Phys. Educ. Rev. 2002; 8:157–75.

35. Fernhall B, Mendonca GV, Baynard T. Reduced work capacity in individuals with Down syndrome: a consequence of autonomic dysfunction? Exerc. Sport Sci. Rev. 2013; 41:138–47.

36. MendoncaGV, Santos I, Fernhall B, Baynard T. Predictive equations to estimate peak aerobic capacity and peak heart rate in persons with Down syndrome. J. Appl. Physiol. (1985). 2022; 132:423–33.

37. Beck VDY,Wee SO, Lefferts EC, et al. Comprehensive cardiopulmonary profile of individuals with Down syndrome. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2022; 66:978–87.

38. Pitetti K, Baynard T, Agiovlasitis S. Children, and adolescents with Down syndrome, physical fitness and physical activity. J. Sport Health Sci. 2013; 2:47–57.

39. Franklin BA, Billecke S. Putting the benefits and risks of aerobic exercise in perspective. Curr. Sports Med. Rep. 2012; 11:201–8.

40. Ataíde SS, Ferreira JP, Campos MJ. Prescription of exercise programs for individuals with autism spectrum disorder: systematic review. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2024.

41. LochbaumM,Crews D.Viability of cardiorespiratory andmuscular strength programs for the adolescent with autism. Complement. Health Pract. Rev. 2003; 8:225–33.

42. Reid P, FactorDC, Freeman NL, Sherman J. The effects of physical exercise on three autistic and developmentally disordered adolescents. Ther. Recreat. J. 1988; 22:2.

43. Pettee Gabriel KK,Morrow JR Jr.,Woolsey AL. Framework for physical activity as a complex andmultidimensional behavior. J.Phys.Act.Health. 2012; 9(Suppl 1):S11–8.

44. Westrop SC, Rana D, Jaiswal N, et al. Supporting active engagement of adults with intellectual disabilities in lifestyle modification interventions: a realist evidence synthesis of what works, for whom, in what context and why. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2024; 68:293–316.

Copyright © 2025 by the American College of Sports Medicine.

Republished with permission.

About the Authors

Benjamin D. Boudreaux Ph.D., is a Clinical Assistant Professor of Exercise Science in the Department of Kinesiology at The University of Alabama. His research area of emphasis lies at the intersection of clinical exercise physiology and physical activity epidemiology with a specific focus examining the association between the 24-Hour Activity Cycle in the prevention and treatment of cardiovascular disease and other health outcomes. Additionally, he has expertise using consumer wearable devices for validation purposes or as a tool to examine different health behaviors in various populations. Beyond his professional efforts, Dr. Boudreaux also regularly advocates awareness for the autism and type 1 diabetes communities, which includes serving as the founder and director for the Growing United in Disability Empowerment (GUIDE) program for the American College of Sports Medicine, collaborating on different scientific statements/presentations, and running the 2023 TCS NYC Marathon and 2025 Boston Marathon.

David S. Geslak, President and Founder: As a Fitness Coordinator at a school for children with autism, Coach Dave experienced first-hand the challenges of teaching exercise. By understanding that students with autism learn differently, he developed a system that has become a breakthrough in effectively teaching exercise. Nine universities have incorporated his program into their Adapted Physical Education and Special Education Programs. As a pioneer in the field, Dave gives his insightful and inspiring presentations around the world, including, Egypt, Dubai, Barbados, Russia, and Canada. Coach Dave is also a published author, writes Autism & Exercise research articles, and has a TV Show “Coach Dave” on the Autism Channel.

Coach Dave graduated from the University of Iowa with a degree in Health Promotion. He is a Certified Exercise Physiologist from the American College of Sports Medicine and a Certified Strength and Conditioning Specialist from the National Strength and Conditioning Association. He is a former assistant strength and conditioning coach for the University of Iowa Football Program and co-founder/President of Right Fit. He is also a member of the State of Illinois Autism Taskforce.