Dr. P.H. Skinner: Controversial Educator of the Deaf, Blind and Mute…

…and Niagara Falls, New York Abolitionist

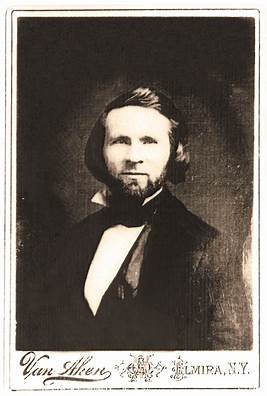

Dr. Platt Henry Skinner. Photo courtesy of Gallaudet University

By Michael B. Boston, PhD

Many Americans who worked to abolish the institution of slavery are unknown or forgotten. Some of them were "conductors" of the celebrated Underground Railroad. Some supported the abolition movement with financial contributions. Others secretly, and sometimes openly, taught fugitives and free blacks how to read and write, often to the displeasure of their communities. Collectively, they were the force that demanded that their elected representatives end slavery. Without their courage and persistence, slavery might have lasted much longer.

P. H. Skinner1 (or: Dr. Platt Henry Skinner) was one of those unsung individuals, who was vehemently opposed to slavery and expressed his views vocally and in print. Moreover, evidence indicates he may even have participated in Underground Railroad activities in Niagara Falls, New York, one of the final stations on the journey to freedom. Nonetheless, most sources documenting Skinner's activities underscore his role as an educator and a controversial figure.

We first encounter Skinner in 1856 in Washington, D. C., when he appeared in Washington with five children who were deaf, blind or mute.2 He had brought these children with him from Canada via New York State. They were the children of fugitive slaves and had been born in Canada. When he came to Washington, Skinner had plans for establishing a school for deaf, blind and mute children. He let his ideas be known, and he attracted the attention of Amos Kendal, a journalist, businessman and Democratic politician, whose wife was deaf. Kendal, who was about seventy when he met Skinner, had been a key member of President Andrew Jackson's cabinet.3 Kendal helped Skinner to acquire "a house and two acres, helped him set up a board of directors, and introduced a bill in Congress, which rapidly passed, incorporating the Columbian Institution for the Deaf and Dumb and the Blind, and providing an allowance of $150 a year for each local child admitted.4 To make the public aware of the school, Skinner or Kendal announced in an advertisement in The National Era, a local Washington newspaper, that Friday afternoon of each week would be set apart for the reception of visitors at the Institution.5 They also invited their friends. Other advertisements to make the public aware of the school were also published from time to time.6

A few months after the school opened, a washerwoman of one of Kendal's friends, who had a son in Skinner's school, complained to her employer that her son had been badly cared for and neglected. Her employer informed Kendal, and Kendal and another board member immediately went to the school. The school's door was locked and the children that were there did not know how to unlock it. Kendal and the board member knocked the door down and entered the school. There they observed that the children had indeed been neglected, and two of them lay on a pallet, moaning. The children appeared to have been suffering from heat exhaustion. It is not clear if Skinner was in error, but he appeared to be responsible. Kendal sued in court and obtained custody of the five children Skinner had brought from New York, while the other children were temporarily returned to their parents until Kendal found a new school principal and building.

Skinner, however, protested and put up a strong fight, arguing that his students were not badly cared for or neglected, and that he was being persecuted, not only due to a misunderstanding, but also because he was a northerner and an abolitionist who taught and practiced equality at his school. He allowed black children to eat at his table with him, and he taught black and white mute and blind children together in his school on equal terms.7

The fact that Skinner was raising equality issues in Washington should be understood fully in the context of the times.8 Up until 1850, the domestic slave trade was practiced extensively in Washington, and indeed the city was a major slave-trading center. As foreign diplomats traveled throughout the capital, they could see ample evidence of the slave trade: Africans sold on auction blocks, chained and shackled, and held in pens. It was not until the Compromise of 1850 went into effect that the slave trade was "legally prohibited" in the nation's capital. However, while Skinner was teaching in his integrated school, persons of strong pro-slavery sentiment may have been disturbed by Skinner's social practices.

Nonetheless, Skinner was dismissed from his position, labeled in local newspapers as an irresponsible imposter, and held in disrepute throughout much of Washington. He appeared in court at least twelve times, mainly attempting to regain guardianship of the five children he had brought from New York. Finally, in an attempt to crush his resolve, the building that contained his school and family was burned to the ground, and he and his wife and infant, and a fellow-teacher, were forced out of their home at three o'clock on a cold April morning.9

Undoubtedly this event contributed toward convincing Skinner that he must abandon his plans for establishing his school in Washington, and look for another location. According to his detractors, he illegally took custody of his five students and fled to Baltimore. Defending his actions, Skinner argued that the courts of the District of Columbia did not have jurisdiction over his five students.10 He claimed that only New York State did, and that New York State, as well as the parents of the five students, had given him guardianship of the children. Consequently, when he left Washington, Amos Kendal and other board members of the Columbian Institution for the Deaf and Dumb and the Blind held him in contempt, and their opinions of him would have a negative effect on Skinner's image and his future endeavors.

In 1858 Skinner was in the village of Suspension Bridge, New York, which today is a section of Niagara Falls, New York.11 It was through Suspension Bridge that many fugitive slaves passed on the "underground railroad" on their way to Canada. In Suspension Bridge there was a railroad bridge that connected the village with Canada. Many an abolitionist rode the train over that bridge together with their cargo of fugitive slaves, leading them to freedom.12 On one of her journeys, Harriet Tubman accompanied Joe, a fugitive slave, across that bridge to Canada. Upon reaching the Canadian side, she rushed across the aisle, shook Joe and shouted, "You've shook de lion's paw. Joe! You're a free man, Joel Come and look at the Falls!"13 Joe broke down in tears and praised and thanked God.

Suspension Bridge and other villages and cities in Niagara County were rife with abolitionist and states' rights factions.14 The Niagara City Herald, a local Suspension Bridge newspaper, supported the states' rights position that it was for the state to decide whether or not to permit slavery. In Lockport, the county seat, frequent conflicts occurred between the abolitionists and the slavery supporters.15 Suspension Bridge and Niagara Falls residents involved in the tourist industry were mindful that a number of wealthy plantation owners frequented the Niagara Falls area, sometimes accompanied by one or two of their slaves. They were reluctant to lose the revenue from such tourists, by promoting anti-slavery issues, and Skinner, undoubtedly, must have been aware of this.

“The number of students in The School for Colored Deaf and Dumb and Blind Children ranged from about 9 to 15, with students of various ages in attendance. In 1860, for example, nine students were attending the school. Six of them were from Canada, one from New York State, one from New Jersey, and one from Pennsylvania. The oldest student was eighteen and the youngest was five. As mentioned earlier, Skinner generally wanted to increase his enrollment because he believed there was a great need for his school. ”

Upon arriving in Suspension Bridge, Skinner quietly went about the business of re-establishing his school, renting a building and continuing to teach the five children under his tutelage with hopes of expanding his school. He named his new school, "The School for Colored Deaf and Dumb and Blind Children." Unlike his school in Washington, his Suspension Bridge school was strictly for black children who were deaf, mute or blind, for he reasoned that such children were more deprived and neglected, desperately in need of education and training. In support of this, he wrote:

It [the new school] is not intended to take any child whose education is provided for in any other way. The school was at first established for the children of fugitives; but, since its commencement, it has been thought best to open its doors to all such mute and blind colored children as are not provided for otherwise, as far as the means of the school will permit. The command given is, "Go into all the world, and preach the gospel to every creature." -- This command seems to reach the lowest of all God's creation.... The credentials which are necessary for admission into this school, then, are,

1st. A dark face.

2nd. Deaf ears and a mute tongue, or blind eyes.

3d. That the state or county in which they live has not provided for their education.16

As he did in Washington, Skinner solicited the formal support of churches, and persuaded the Congregational Church of Niagara City (a new but temporary name for Suspension Bridge) and the Presbyterian Church of Niagara Falls to provide formal support for his school.17 The Presbyterian Church of Lockport would later grant its formal support as well.

Skinner served as principal and instructor of his new school, which was a boarding school like the school he had in Washington. In regard to his training, he had had some connection with the New York Institute for the Instruction of the Deaf and Dumb. Jarusha Skinner, his wife, was also an instructor at the new school and a graduate of the same New York Institute.18 After graduating she was a teacher at her alma mater for seven years. The Skinners, who had first met at the Institute, were the backbone of their new school, working hand-in-hand to make it successful.

The school's main objective, according to Skinner, was to teach its students about Christianity. Skinner, a paternalistic and religious person, saw deaf, blind and mute uneducated black children as heathens, existing in a life of darkness, of no concern to most people, and if not helped they were assured a place in Hell in the afterlife. However, he believed that, before he could teach his handicapped black children about Christianity, he had to equip them with means of communication. "We must teach the hand of the mute to perform the office of the tongue, and the eye to perform the office of the ear; the fingers of the blind must be taught to see."19 Subsequently, Skinner and his wife taught their students sign language and Braille, and other skills that would enable their students to cope in the world.

The number of students in The School for Colored Deaf and Dumb and Blind Children ranged from about 9 to 15, with students of various ages in attendance.20 In 1860, for example, nine students were attending the school. Six of them were from Canada, one from New York State, one from New Jersey, and one from Pennsylvania.21 The oldest student was eighteen and the youngest was five. As mentioned earlier, Skinner generally wanted to increase his enrollment because he believed there was a great need for his school. However, lack of funds was always the reason given for his school's small enrollment, but Skinner and his wife felt that they were nevertheless providing a valuable service to their community and society.

Skinner did not charge his students tuition to provide funds to operate his school because he knew they were impoverished. Although in Washington Congress appropriated $150 per year for each local child attending the Columbian Institution for the Deaf and Dumb and the Blind, and also permitted school officials to collect philanthropic donations, Skinner and his wife had to bear the burden of all their expenses. They relied entirely on donations from surrounding communities. Being a religious man and affiliated with many Christian churches, it was Skinner's practice to visit churches and other venues in surrounding areas and beyond, and to ask to be allowed to plead to their congregation for support. Skinner would generally take three or four of his students and have them exhibit some of the things they learned at school, such as praying in sign language, reciting the Lord's Prayer, or reading Braille. "During the first six months, from the first of January to the first of July, [Skinner spoke] in various places, under different circumstances, one hundred and thirty-four times, in churches, seminaries, academies, colleges, universities, Sabbath schools, on steamboats and rail-cars...[ceasing] not to plead [the school's] cause, day or night."22 The people would usually be astonished by these displays of learning, presented by a group of ill-favored, downtrodden children. Once people's interest was aroused, Skinner might ask them:

The great question now being solved is, shall the unfortunate deaf and dumb or blind colored children be educated, or not? May we not expect an answer from some friends of the unfortunate? Shall we increase our number, or not?23

Observing the children and hearing Skinner's plea would usually elicit some kind of offering, usually a good one.

After about six or seven months of operating the school, Skinner published a semi-annual report concerning its accomplishments. Although the report shows July 30, 1858 as its publishing date, it was actually published later. It served as a fundraising tool and as a public acknowledgment of donations received. Its production was probably a response to one of Skinner's Washington critics who stressed that while in Washington Skinner never gave an accounting of the funds he collected.24 Nonetheless, it is evident from this report that he had traveled near and far to plead his cause, visiting such places as Lockport, Buffalo, Wilson, Leroy, Albion, Fredonia, Westfield, Batavia, Canandaigua, Coming, Lima, Cleveland Ohio, Chatham and St. Catherines in Canada, and so forth.25 In addition to collecting funds, Skinner also accepted provisions that would help maintain his students and school, such as food, clothing, furniture, bedspreads, and other household goods.26 Despite aggregate donations of $577.67 for the first six or seven months of operation, Skinner listed the school's expenses at $620.59, reflecting a deficit of $42.92, leading to another appeal for funds. Money was always a vital issue with his institution.

Up until this point, Skinner was virtually unknown to most people in Suspension Bridge and other sections of Niagara Falls. According to Skinner, upon arriving in Suspension Bridge most of his attention was given to re-establishing his school and to his family.27 Within a six-month period he attended local churches for a total of perhaps six times, and he did not ask any citizens of Suspension Bridge or the near surrounding area for funds.28 Moreover, at that point he did not recruit any local children to attend his school, nor did he contact local elites to ask for their advice and endorsement of it. His institution was practically an unknown entity in a community that was widely known for its tourist industry and the majestic beauty of its cataract, and minimally known for its role in the Underground Railroad.

Then one day, according to Skinner, he attended a local Sunday school and told the children there of his trials and tribulations in Washington, while explaining his life purpose of educating "the least of these" -- "the deaf, mute and blind children of the despised colored race."29 He called his persecutors satanic and said that he was persecuted because he was a northern abolitionist who believed in and practiced equality toward all of God's creatures. His beliefs reflected the biblical teaching, that whatever you do to the least of Christ's brethren, you do it to him [Mt 25:40].

In fact, my primary source literature (newspapers, reports, personal writings, etc.) suggests that Skinner indeed presented himself as one who was persecuted like Jesus Christ --persecuted for performing a courageous, unpopular but necessary service. Whenever he responded to his enemies' attacks, this is the general posture he assumed. He seems to have felt that he, like Christ, was doing a righteous act, and for that he expected to be much maligned -- even crucified. Being a religious, church-going person, Skinner seemed happy to carry his cross, possibly because he believed he would receive his reward in the after-life. He seemed to be glad to walk in his Savior's footsteps.

That day, Skinner relates, one or more of the children went home and told their parents what he had said.30 One of these parents, who was influential in the community, was alarmed by the story that his child related and began to investigate to find out who Skinner was. This investigation occurred seven months after Skinner had been living and working in Suspension Bridge.31 This parent wrote a letter to one or more individuals in Washington, inquiring about Skinner. One or more of these letters happened to be received by one of Skinner's powerful enemies--Amos Kendal, the influential Washington Democrat. As noted earlier, when Skinner left Washington, he did not leave in favorable circumstances. He had made powerful enemies in Washington who felt that, though Skinner's home had been burnt down and he had been forced out of town, he deserved such treatment. They believed he was a swindler and an imposter who had escaped their grasp, and who should have been jailed long before. Accordingly, the report about Skinner that was given to this probing parent was hardly a favorable one. Kendal made 22 charges, with some redundancy, against Skinner, which are listed below:

(1) He only desires to use names of responsible citizens as a means to raise money for which he never intended to account.

(2) I feel it my duty to denounce him as an imposter.

(3) He uses his train[ed] children for the sole purpose of raising money for his own use.

(4) He is a lying imposter.

(5) He exhibited his children through a large portion of N.Y. collecting money on false pretenses.

(6) He claimed to be an agent of the New York Inst. for the Deaf and Dumb.

(7) He repeated an infamous falsehood.

(8) His detection in a gross falsehood induced me to publish him as an imposter.

(9) When it was proposed to put him under regulations requiring him to account for all

moneys collected, it was found he had no intention to account.

(10) He wanted the use of our names to facilitate his impositions on our fellow citizens.

(11) It was ascertained that he treated the poor mutes in his possession most brutally.

(12) He fed them with scanty and improper food.

(13) He furnished them with insufficient clothing.

(14) He treated them most brutally.

(15) All this was proven in court.

(16) Dr. S. procured the children to be run off to Baltimore.

(17) He was indicted for perjury.

(18) He was sent to jail for contempt of court.

(19) It was surely no persecution to let him go unscathed of justice.

(20) He tells atrocious lies to operate on the sympathies of men and women.

(21) He thus picks their pockets.

(22) He is accompanied by three or four [sic] negro children to give effect to his imposture.32

This critique of Skinner's character, representing his past, whether true or not, would follow him and precede him throughout much of Niagara County and other towns and villages near and far.

The concerned parent that received this unflattering report from Kendal was evidently alarmed. Being an active influential citizen of his community, he took it upon himself to warn the public about Skinner. He had published Kendal's letter and other unsettling reports from Washington about Skinner in the Niagara City Herald. The relationship of this parent to the Herald is not clear. It is not known whether this parent was an owner, employee, or board member of the Herald or just an independent party who was allowed to freely use the Herald as an instrument to publish his warning letters. This concerned parent wrote numerous letters in the Herald -- first giving warnings about Skinner then attacking him. At the end of his letters, he always wrote "Mr. Justice," rather than revealing his true name.

In August of 1858, the Niagara Falls Gazette, another local paper, published a story involving the attacks on Skinner's character. It stated that the Herald had been engaged for several weeks in "smoking out" a Dr. Skinner, and that the paper had published the letters from the Hon. Amos Kendal, the Rev. B. Sunderland, the Rev. Gurley, the Rev. L. M. Pease, and an Hon. Mr. Dean, all with the intent of proving that Skinner was an imposter and should not be supported.33 Moreover, the article stated that Skinner refused to reply to those charges through the Herald and that he threatened another newspaper, the Lockport Courier, with a libel suit. The Gazette, which tried to be neutral, stressed that there was a better method for Skinner to meet his attackers, if the charges were untrue.34 "At least it would look much better to take care of the Herald, which opened the discussion, before going abroad to find a subject for a libel suit."35 By and large, the Gazette felt that the charges against Skinner were pretty damaging, implying that perhaps he was guilty. Then again, due to Skinner's unwillingness to be associated at all with the Niagara City Herald, the Gazette did allow him to respond to his detractors through its pages.

Skinner, who was taken aback by the attacks, rushed to respond to "Mr. Justice," who had placed him under such intense public scrutiny. In eight lengthy articles, published from November of 1858 to January of 1859, Skinner passionately argued his case.36 First, Skinner characterized all of his attackers as Democrat defenders of slavery, who were obsessed with ending a school such as his that sought to advance black children. Secondly, he argued that all of his attackers were really agents of Amos Kendal and that by doing his bidding they hoped for a favor from him. Skinner provided no evidence for this claim. To buttress this point, Skinner made the case that his attackers were mere acquaintances of his (Kendal and Sunderland) or perfect strangers (Gurley, Pease, Dean and Mr. Justice), individuals who did not know him or his work. Thirdly, Skinner stressed that not one of the numerous charges made against him in Washington had held up in court, a court system that he judged to be biased toward slavery. Fourthly, in response to Mr. Justice signing his entire letters "Mr. Justice," Skinner signed his as "Truth." Then he challenged "Mr. Justice" to reveal himself, particularly if he felt assured of the charges he had made against him and particularly since he did not attend a public meeting called by Skinner to confront his critics. In defending himself, Skinner wrote:

We now again politely ask Justice for his name. If he is so respectable a citizen as he says he is we should like to form his acquaintance. By giving his name to the public he may possibly be believed by some. Come, Mr. Justice, give us your name, we are anxious to learn the names of all the respectable men in the community.37

Throughout his writings, "Mr. Justice" continued to reiterate the charges that he had published regarding Kendal's views. He emphasized that he was against Skinner only because he was a swindler and an imposter who was taking advantage of the legitimate sympathies of his community and other communities. He further wrote that he was against slavery in the abstract but that he believed that states should have the right to decide if they wanted slavery in their borders.38

Unfortunately for Skinner, newspapers near and far carried the Niagara City Heralds story about him. The Lockport Daily Advertiser and Democrat initially gave him and his school a favorable report in its columns. Following the Herald's story, they began to examine Skinner more closely, asking him probing questions that were not answered to their satisfaction. They therefore publicly retracted their recommendation of Skinner and, to serve as a warning to their readers, published accounts of other towns and cities that Skinner visited to solicit funds.39 In publishing an account of Skinner's visit to Utica, New York, the Lockport Daily Advertiser and Democrat declared: "When will people learn to remember what they read, and pay attention to gross imposters when the press warns them before hand? [Skinner's] toadyism is convincing of his skill and public weakness."40 The Lockport Courier, the Rochester Union, and the Utica Morning Herald all carried the Herald's story -- even embracing it and defaming Skinner themselves to the point where Skinner filed a libel suit against these papers.41 Other than the Utica Morning Herald, the judge seemed to have agreed with Skinner.42 After this suit, the public attacks on Skinner seemed to have decreased. Regardless, Skinner's reputation was damaged in Niagara County and other parts of New York State and Canada.

As an example, one Sunday morning, Skinner, accompanied by a Mr. John L. Felter and some of his pupils, attended a church in St. Catharines, Canada to inform parishioners of his work and to solicit aid for his school. Mr. Felter was a neighbor of Skinner's. St. Catharines, which was thirteen miles from Suspension Bridge, was amenable to a message of the kind that Skinner would present. It was a community well aware of the treatment of slaves and free blacks in the United States because a large fugitive slave community resided in the town.43 Harriet Tubman even lived and worked in the town for a while. Moreover, some of Skinner's pupils may have been from St. Catharines. Skinner, as usual, went through his routine of exposing his students and their needs to his attentive audience. He spoke with great interest regarding the students under his tutelage, stating that they belonged to a despised race and that they were the most unfortunate of the despised. The blind children read from Psalms by raised letters, and a deaf and dumb child repeated the Lord's Prayer by signs.44 The audience was mesmerized. Then Skinner asked those who thought those poor children should know there is a God to aid him.45 At that juncture, a man by the name of H. S. McCollum, who resided in Skinner's community, came to the podium and recounted Skinner's troubles in Washington. He stated that he knew Skinner, and that while Skinner was in Washington, he only had one colored child in his school, and that the colored child was taken due to brutal treatment. He also stated that Skinner was prosecuted by the courts of Washington and that the ministers of the Congregational and Presbyterian churches of Niagara City were against him.46 In rebuttal Skinner stood up and said that he did not know this man who was attacking him and that he had never seen him before in life. Concluding, he stressed that McCollum was trying to keep bread from the mouths of the poor, deaf, dumb and blind children. Skinner would later argue that McCollum had some associations with Kendal and Justice. With these continuous attacks on his character, even the Niagara Falls Gazette, a newspaper that had initially allowed Skinner to defend himself through its columns, began to distance itself from Skinner and even attack him, primarily after he started his own newspaper and made some negative remarks about the Gazette,47 asserting that that paper was proslavery.

Skinner's paper was launched in about February of 1859, thirteen months after his arrival in Suspension Bridge.48 It was part of the "silent press" of the nineteenth century, a press that focused on concerns and needs of the handicapped. He called his paper The Mute and the Blind and proudly announced that the editor of the paper was a blind man; the compositors were deaf and dumb; the blind performed the presswork; and the papers were folded by the blind and wrapped by the mute.49 The Mute and the Blind was a semi-monthly publication, which sold for $1.00 per single copy and ten copies to one address for $5.00. It was obviously a fund-raising mechanism. Skinner's aim in publishing this paper was to inform the public of his school's works and needs and to plead his case. It gained a readership in Niagara County and beyond. Even many of Skinner's adversaries read his paper, often writing disclaimers to stories that he had written.50

The Mute and the Blind concretely espoused Skinner's philosophy and further conveyed that he was a religious man who believed strongly in the "Ten Commandments." Each copy of The Mute and the Blind had some moral lesson for adults, parents and children, encouraging children to honor and listen to their parents so that their days on earth would be long, and encouraging parents to be to their children the parents that God had commissioned them to be. His paper also had health lessons, such as the proper amount of sleep and nutritional issues. Another favorite topic of Skinner's was the institution of slavery. He conveyed its horrors to readers and argued that all of God's creatures were equal and had a right to life and liberty. During the Civil War, he clearly let his allegiances be known, as he kept abreast and wrote about the successes of the Union army.51

Other topics that he discussed, which were manifestations of his philosophy, were poverty and wealth, proposed prayer weeks, announcements about other anti-slavery spokesmen along with sympathies for these same individuals when they were persecuted for making public their stances, temperance issues, poetic works that reflected moral and abolitionist issues, the slave trade, ideas for reconstructing the South after the Civil War, Negro colonization, life in other cultures, various animals of the world, and so forth.

Skinner would publish The Mute and the Blind in Suspension Bridge for about three years. Simultaneously, he, his wife and sometimes an additional teacher, worked to ensure that their boarding school was operative. Skinner seemed always to be able to find just as many individuals to compliment him and his school as those that had attacked it.52 For his school's first sixth-month evaluation, an evaluation committee, consisting of Pastor Alexander McColl of the Presbyterian Church of Suspension Bridge and Pastor Derwin W. Sharts of the Congregational Church of the same town both gave The School for Colored Deaf and Dumb and Blind Children favorable recommendations.53 After March of 1861 however, Skinner slowly faded from public attention in Niagara County. His name rarely appeared in local papers after that date.

In 1862 Skinner emerged in the Trenton, New Jersey area, and he would continue to publish The Mute and the Blind from there. Evidence tends to indicate that he left the Niagara County area in order to operate in a less hostile environment,54 especially since he depended exclusively on public funds to maintain his school. Moreover, his health and eyesight were worsening, perhaps due to the stress and strain he experienced first in Washington, then in the Niagara County region. His enemies, of course, would underscore that he was searching for a new naive public to swindle. Skinner would live and work in the Trenton area for about four years, apparently also making friends and enemies there. He died in 1866, leaving a wife, a son, and a struggling school, which was burnt down by incendiaries following his death, causing his wife to abandon her determination to keep his dream alive.55 "Some of the children belonging in Canada were taken home...by Mr. D. J. Farrington, brother of Mrs. Skinner."56 And Mrs. Skinner and her son went to live with her brother in Coming, New York.

How should Skinner be evaluated? Was he an imposter and a swindler or was he a much-maligned man? It is evident that Skinner was a determined, blunt, outspoken man, unmoved by the taunts, influence and power of his adversaries. He made his goals and plans known and stood by them. He possessed a personality that made individuals either like or detest him. Evidence indicates repeatedly that this was the sort of emotion that was evoked in people who encountered him. After interacting with him, they rarely departed with a feeling of indifference about him. Being a Christian, Skinner interpreted the prosecution that he faced as a price to be paid for being right and walking in the footsteps of his Savior -- Jesus Christ.

The attacks on Skinner's character in Suspension Bridge stemmed from Amos Kendal's letter charging Skinner with numerous violations. None of Kendal's charges held up in court. Nonetheless, citizens of influence in Niagara County used that information to define who Skinner was to the public. Of all the available primary source data, only one charge against Skinner was perhaps substantiated, and that was a charge that the Lockport Daily Advertiser and Democrat made. They charged that Skinner represented his wife as deaf and mute to them but that, in fact, she could actually hear and talk.57 Skinner, conversely, passed this off as a misunderstanding. From examining the Lockport Daily Advertiser and Democrat's published account of the incident, it is evident that they were influenced by Kendal's letter, as well as those of "Mr. Justice," and that they were searching for faults. Skinner's fault appears to have been that he was initially an unknown and an outsider who failed to get the consent of certain influential individuals before operating his school in their community and possessing a strong-minded personality.

However, Skinner did have his faults, which contributed toward the attacks that he suffered. Whenever he was attacked in the press, he tended to label all of his adversaries as members of the Democratic Party, defenders of slavery, and racists. These rebuttals were not always substantiated. Skinner's business practices were also irregular at times. He promised, for instance, a Mr. Wright of Utica, a "Certificate of Life Membership" to his school after his Sunday school donated $10. In theory certificate holders could vote at board meetings. Mr. Wright did not receive this certificate and inquired about it. Skinner replied that he had not ordered the engraving for the certificates because he was forced to use all funds to clothe and feed his deaf, dumb and blind students.58 Evidently being upset, Mr. Wright allowed the Niagara City Herald to publish Skinner's reply. Another case occurred when Skinner published the first semi-annual report of his school; he acknowledged that the reported contributions for citizens that lived in Wilson might be wrong.59 He asked those citizens to inform him of his possible mistakes, and he would publish a correction in the next report. Moreover, Skinner relied exclusively on public donations and the proceeds from his paper to finance his school. This was a grave error. More self-help efforts might have silenced many of his critics. To go throughout Niagara County and beyond, generally every Saturday or Sunday, to beg for funds would exhaust any community, especially if it could not see its donations being put to good use, as in the Mr. Wright case. In contrasting Skinner's fund-raising methods with those of Booker T. Washington, the founder of Tuskegee Institute we find that, like Skinner, Washington asked for donations. However, the donations that he received along with his toil could be readily observed in purchased land, numerous school buildings, on-campus businesses, farm animals, students, and teachers, all which ultimately resulted in a multimillion-dollar institution.

In sum, it is correct that Skinner never had more than 9 to 15 students attending his school at one time. Nevertheless, he, his wife and others, sincerely endeavored to educate their pupils, contributing toward making them more involved citizens. They were engaged in a self-sacrificing, unpopular task of assisting a much-despised race and an unfortunate and neglected group within that race. They should be commended and remembered for their labors.

Furthermore, in regard to slavery, Skinner was an abolitionist and activist. He boldly let his views be known, orally and in print, whether he was in Washington, Suspension Bridge or Trenton. Being a promoter of equality for all racial groups, he supported the anti-slavery activities of others and may have even been a conductor on the Underground Railroad. He resided at one of the terminuses of the Underground Railroad (Suspension Bridge) and interacted with fugitive slave communities in Canada, even bringing back some of their children to the States to be educated, as several of their parents worded that their children might be caught in the clutches of slavery. Consequently, the controversial abolitionist educator, Dr. P. H. Skinner, was definitely no enigma; although at times he was misunderstood, his personality made him either friends or enemies at a volatile time in United States history.

References

(1) "P. H. Skinner," instead of Platt Henry Skinner, will be used throughout this article because that is how Dr. Skinner's name appears in his and other published writings. Moreover, the author would like to thank H. William Feder for informing him that P. H. Skinner lived and worked in Niagara Falls, New York.

(2) Jack R. Gannon, Deaf Heritage: A Narrative History of Deaf America (Silver Spring, MD: National Association of the Deaf, 1981), 276-277.

(3) Ibid., 276.

(4) Ibid., 276-277: "Trustees Wanted," The National Era, 27 November 1856, 191.

(5) "Institution for the Deaf, Dumb, and Blind," The National Era, 26 June 1856, 103.

(6) "Education of the Deaf and Dumb," The National Era, 11 September 1856, 147

(7) "Dr. Skinner's School," Niagara Falls Gazette, 8 December 1857, 2.

(8) William T. Laprade, "The Domestic Slave Trade in the District of Columbia," Journal of Negro History, Vol. 11. No. 1 (January 1926), 17-36.

(9) "Dr. Skinner's School," Niagara Falls Gazette, 22 December 1858, 2.

(10) "Dr. Skinner's School," Niagara Falls Gazette, 8 December 1858, 2.

(11) Suspension Bridge (or Niagara City) and the Niagara Falls of old would combine in the late 1800s to form the area that is known as Niagara Falls today.

(12) "Underground Railroad," Niagara Falls Gazette, 13 June 1860; "Underground Railroad," Niagara Falls Gazette, 22 September 1858, 3; "Underground Railroad," Niagara Falls Gazette, 22 April 1857, 3; "Flight in Canada," Niagara Falls Gazette, 28 February 1895, 3; "Niagara's Role in Underground Railroad Cited," Niagara Falls Gazette 23 March 1991, 5A

(13) "Tubman led Slaves to Falls' Freedom Gate," Black History Folder, Local History Department, Niagara Falls Public Library.

(14) "Slavery Became Big Issue in County as Early as 1834, Historian Reports," Black History Folder, Niagara County Historical Society, Lockport, New York; David L. Dickinson, "African Americans in 19th Century Lockport.

(15) "Lockport Was Active in Fighting Slavery," Niagara Falls Gazette, 7 May 1958, 32; "Gov. Hunt Said States Must Settle Slavery," Black History Folder, Niagara County Historical Society, Lockport, New York; David L. Dickinson, "African Americans in 19th Century Lockport," Niagara County Historical Society, Lockport, New York.

(16) "The First Semi-Annual Report of the School for the Instruction of the Colored, Deaf, Dumb, and Blind," 8.

(17) Ibid., 5.

(18) "Dr. Skinner's School," Niagara Falls Gazette, 17 November 1858, 2.

(19) "The First Semi-Annual Report of the School for the Instruction of the Colored, Deaf, Dumb, and Blind," 8.

(20) H. William Feder, The Evolution of an Ethnic Neighborhood that Became United in Diversity: The East Side, Niagara Falls, New York 1880-1930 (Ph.D. diss., University of Buffalo, 1999), 601

(21) Ibid. 601

(22) "The First Semi-Annual Report of the School for the Instruction of the Colored, Deaf, Dumb, and Blind," 8.

(23) Ibid., 10.

(25) "The First Semi-Annual Report of the School for the Instruction of the Colored, Deaf, Dumb, and Blind," 10-15.

(26) "We Have the First Semi-Annual Report of the School for the Instruction of the Colored Deaf, Dumb, and Blind." Niagara Falls Gazette. 17 November 1858, 3.

(27) "Dr. Skinner's School," Niagara Falls Gazette, 17 November 1858, 2.

(28) Ibid., 2.

(29) Ibid., 2.

(30) Ibid., 2.

(31) "Dr. Skinner," Niagara Falls Gazette, 11 August 1858, 3.

(32) "Dr. Skinner's School," Niagara Falls Gazette, 8 December 1858, 2.

(33) "Dr. Skinner," Niagara Falls Gazette, 11 August 1858, 3.

(34) Ibid., 3.

(35) Ibid., 3.

(36) "Dr. Skinner's School," Niagara Falls Gazette, 17 November 1858, 2; "Dr. Skinner's School," Niagara Falls Gazette, 24 November 1858, 2; "Dr. Skinner's School," Niagara Falls Gazette, I December 1858, 2; "Dr. Skinner's School," Niagara Falls Gazette, 8 December 1858, 2; "Dr. Skinner's School," Niagara Falls Gazette, 15 December 1858; "Dr. Skinner's School," Niagara Falls Gazette, 22 December 1858, 2; "Dr. Skinner's School," 29 December 1858, 2; "Dr. Skinner's School," Niagara Falls Gazette, 5 January 1859.

(37) "Dr. Skinner's School," Niagara Falls Gazette, 15 December 1858, 2.

(38) "Dr. Skinner's School," Niagara Falls Gazette, 5 January 1859, 2.

(39) "Dr. Skinner, The Philanthropist," Lockport Daily Advertiser and Democrat," 16 August 1858, 3; "The Mute Teacher," Lockport Daily Advertiser and Democrat, 9 February 1859, 3; "Skinner at Utica," Lockport Daily Advertiser and Democrat, 17 March 1859, 3.

(40) "Skinner at Utica," Lockport Daily Advertiser and Democrat, 17 March 1859, 3.

(41) "Libel Suits," Niagara Falls Gazette, 6 April 1859, 3; "Libel Suit," Lockport Daily Advertiser and Democrat, 5 April 1859, 3.

(42) "Platt H. Skinner, the Deaf & Dumb School Teacher at the Bridge," Lockport Daily Advertiser and Democrat 21 October 1859, 3.

(43) Benjamin Drew, Fugitive Slaves in Canada (Boston: John P. Jewett and Company, 1856), 17-93.

(44) "Dr. Skinner's School," Niagara Falls Gazette, 15 December 1858, 2.

(45) Ibid., 2.

(46) Ibid., 2.

(47) "Libel Suits," Niagara Falls Gazette, 6 April 1859, 3; "The Niagara City Herald Published a Letter Addressed to a Mr. Wright," Niagara Falls Gazette, 4 May 1859, 3; "How a Blind Editor Raves," Niagara Falls Gazette, 13 July 1859; "Still Harping," Niagara Falls Gazette, 26 July 1860, 3; "The Editor of the Mute and the Blind is a Monomaniac," Niagara Falls Gazette, 20 March 1861, 3.

(48) "The Mute and the Blind," Niagara Falls Gazette, 23 February 1859, 3.

(49) The Mute and the Blind, Vol. II, Niagara Falls, & Suspension Bridge, 3 November 1860 (Niagara County Historical Society, Lockport, New York), 100.

(50) "Local and Vicinity News," Niagara Falls Gazette, 20 February 1861, 3.

(51) The Mute and the Blind, Vol. IV, Trenton, N. J., 26 April 1862 (Kroch Library at Cornell University, Ithaca, New York), 56-57.

(52) "Dr. Skinner's School," Niagara Falls Gazette, 29 December 1858, 2; "Dr. Skinner's School," Niagara Falls Gazette, 5 January 1859, 2.

(53) "Report of the Committee of Examination," The Mute and the Blind, Vol. II, Niagara Falls, & Suspension Bridge, 3 November 1860 (Niagara County Historical Society, Lockport, New York), 101.

(54) The Mute and the Blind, Vol. IV, Trenton, N. J., 26 April 1862 (Kroch Library at Cornell University, Ithaca, New York), 59.

(55) "Dr. Skinner's Death," Niagara Falls Gazette, 14 February 1866, 3.

(56) Ibid., 3.

(57) Dr. Skinner, The Philanthropist," Lockport Daily Advertiser and Democrat, 16 August 1858, 3.

(58) "The Niagara City Herald Publishes a Letter," Niagara Falls Gazette, 4 May 1895, 3.

(59) "The First Semi-Annual Report of the School for the Instruction of the Colored, Deaf, Dumb, and Blind," 16.

Article copyright Afro-American Historical Association of Niagara Frontier, Inc.

Afro - Americans in New York Life and History;

New York Vol. 29, Iss. 2, (Jul 2005): 45.

(Republished with permission from the author)

About the Author

Michael B. Boston, PhD is Associate Professor of African and African American Studies at the College at Brockport, State University of New York. He is the author of The Business Strategy of Booker T. Washington: Its Development and Implementation and Dr. Skinner's Remarkable School for Colored Deaf, Dumb, and Blind Children 1857–1860.