Once Again, a Reminder: Never Meet Your Heroes

By Rick Rader, MD, Editor-in-chief

It was several months ago that I came face-to-face with the realization that our hero, and the namesake of this respected publication, Helen Keller, was a proponent of eugenics.

Pictured: Historic Photo of Eugenic and Health Exhibit

Eugenics was the forerunner of the science of genetics, and it promoted the concept that certain groups of individuals were inferior, and for the good of society, had to be identified, isolated, and eventually eliminated. It was the foundation that the Third Reich and the Nazi movement used to justify their genocide during World War II.

I struggled with how to confront the Keller revelation, how to present it, deal with it, and in fact, justify it. I thought I’d come to terms with it against the backdrop of the times. In fact, I wanted to bury both that part of her legacy and my trepidations on how to approach it. I wrote what I thought was a strong, balanced, and factual article on the subject. Responses from many readers seem to indicate they shared the same concerns and applauded the way I handled it.

I was glad for each passing day where it didn’t rear its ugly head and that demands for changing the name of the journal were never suggested or considered.

Of particular interest in confronting the eugenics movement was that it wasn’t some mandate proposed by a small band of knuckle dragging cave dwellers, but one promoted by America’s most respected thought leaders, social scientists, politicians, judges, legal and religious scholars, and researchers from our most prestigious institutions.

As Edwin Black writes in War Against the Weak, “The American masses were not rising up demanding to sterilize, institutionalize and dehumanize their neighbors and kinfolk. Eugenics was a movement of the nation’s elite thinkers and many of its most progressive reformers.”

Dr. Bruce Kelly is a respected North Carolina physician who stood side-by-side with the founders of the American Academy of Developmental Medicine and Dentistry in our early pioneering work in confronting health disparities. These were the days before disparities became a must-include term in journal articles, health policy reform, and research submissions. He is credited with creating one of the earliest versions of a “Mini Residency in Adult Developmental Medicine '' and was always promoting the wisdom to incorporate, not attach, humanism to medical training and practice.

Last week, Bruce sent me an email, skipping the typical “hopes this finds you well” with this heart pounding announcement: “Didn’t know that Mayo was a eugenics proponent. See attached.”

Mayo and eugenics. The two didn’t seem possible to go together.

But there was no mistaking “who” and “what” he was referring to.

Pictured: The Mayo Clinic

In the annals of American medical heroes, we always cite the Big Four of Hopkins (Johns Hopkins Medical School): Sir William Osler in medicine, William Steward Halstead in surgery, William Henry Welch in pathology and Howard Atwood Kelly in obstetrics and gynecology. They were responsible for advances in medical care, medical education, and medical breakthroughs. Following them it’s obvious to name the Mayo brothers as being all-stars in medicine.

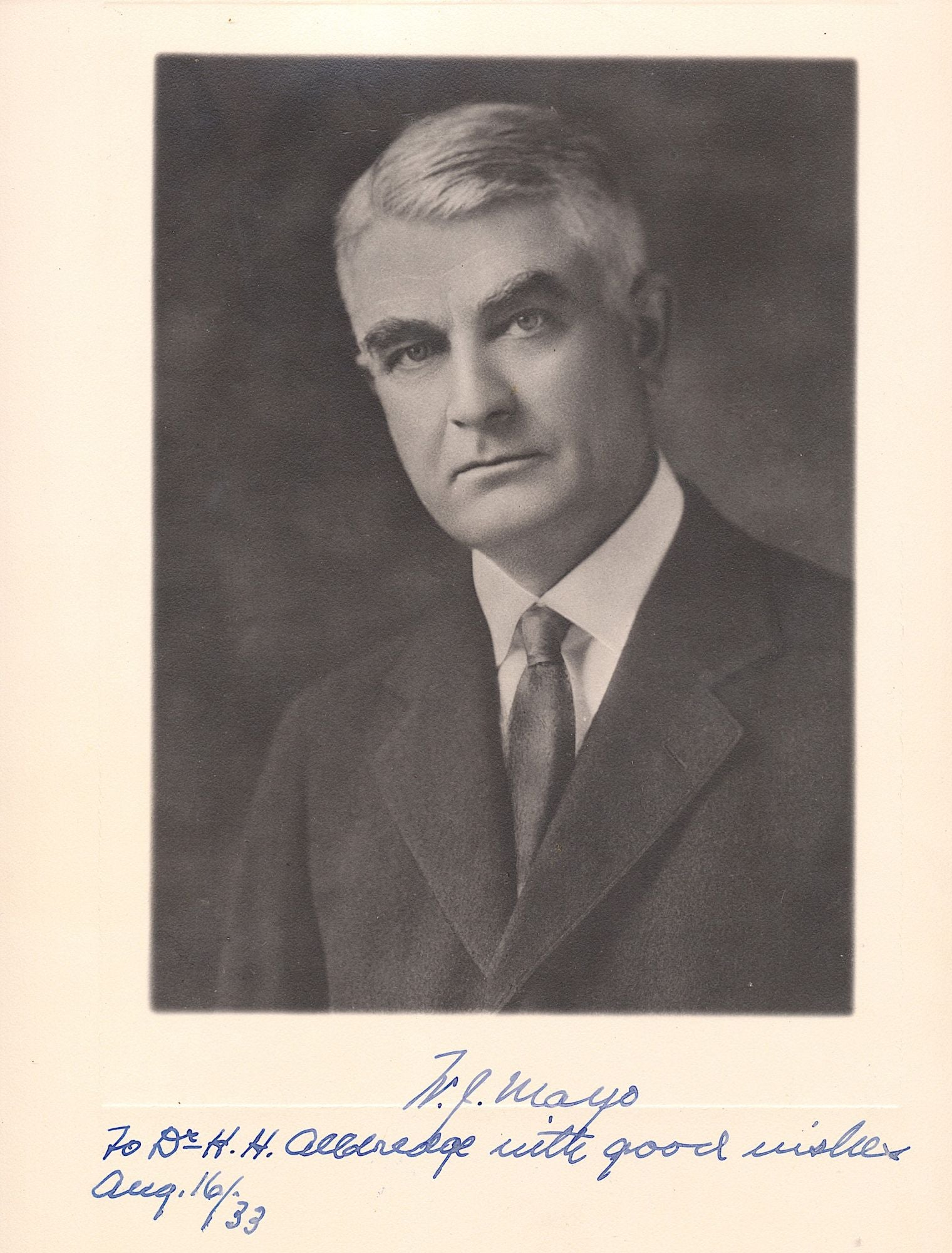

Pictured: William James Mayo

William James Mayo was a physician and surgeon and one of the seven founders of the Mayo Clinic, a name always mentioned in the same breath as asking, “If it was you where would you go?” The Mayo Clinic is typically the answer on the tip of the tongue to that potentially life-saving question.

In 1904 Dr. William Mayo wrote, "My own religion has been to do all the good I could to my fellow men, and as little harm as possible."

It’s distressing to think that the physician who claimed to do as little harm as possible (which is one of the first doctrines of the Hippocratic Oath) fought vigorously to in fact harm people that he identified as being burdens of society.

In a recent New England Journal of Medicine article, Paul A. Lombardo writes about Mayo’s outlook. “Mayo said one goal of public hospitals should be to reduce the number of people whom it must care for at the expense of the taxpayer. A robust sterilization program and limits on immigration of the defective would serve that goal.”

Mayo lectured and wrote vigorously about the search for the final solution of the immigration problem. A major site for his views throughout his lifetime was published in The New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM).

Pictured: The New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM)

Starting in 1812, it has been among the most prestigious peer-reviewed medical journals, as well as being the oldest continuously published one. The Journal not only served as the depository for Mayo’s views on eugenics, but also provided legitimacy and dissemination for an untold number of articles attesting to the menace that the “feeble minded” represented.

To the credit of the current editors and publishers of the NEJM they acknowledge their role in promoting and perpetuating negativistic attitudes about vulnerable populations. They’re doing their best to take responsibility for the journal’s past by prefacing offensive articles with this disclaimer: “This article is part of an invited series by independent historians, focused on biases and injustice that the Journal has historically helped to perpetuate. We hope it will enable us to learn from our mistakes and prevent new ones.”

In essence, that’s what medicine and medical practice is all about—identifying mistakes, taking ownership for them, and ensuring they will not be repeated. That applies to the misdiagnosed atypical presentation of a case of liver cancer to the misguided policy of polypharmacy, diagnostic overshadowing, and rampant ableism.

In essence, that’s what medicine and medical practice is all about—identifying mistakes, taking ownership for them, and ensuring they will not be repeated.

Both Bruce and I struggled to understand how physicians and their ideologies could be hijacked to support the most diabolical (eugenics) treatment directed at fellow human beings.

We rolled out the idea of putting the events in the context of time. Bruce was quick to declare, “The era component though relevant falls short in explanation.” Eugenics remains what it was—a declaration of discrimination, regardless of how the prevailing fears impacted on the comfort of the masses and how it offered a false sense that the onslaught of the imbeciles would be short lived.

The tainted legacy of Keller and Mayo (and countless others) as proponents of curtailing the reproduction of defective family stocks remains a cautionary tale and a reminder that we’re only several generations away from forced sterilizations, lobotomies, human warehouses, chemical restraints, and human experimentation.

I hope I’m prepared for what awaits me in Bruce’s next email.