Overcoming Barriers to Improving Health of Adults with Neurodevelopmental Disorders—Historical Perspective

By Philip May, MD

Director of Quality Improvement & Research International Foundation for Chronic Disabilities, Inc www.chronicdisabilities.org

Clinical Associate Professor of Medicine (Gratis) University of Louisville School of Medicine Louisville, KY

ABSTRACT

“Neurodevelopmental disorders” (NDD) are defined as childhood-onset genetic or acquired chronic health conditions that interfere with various functions of the brain. At least since the late 1800’s, physicians have recognized that persons with neurodevelopmental disorders represent a special population, due to lack of understanding of the causes, complexity, and management of their frequently encountered health conditions. An ACGME approved medical specialty (Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics) which comprehensively addresses these health conditions in children has existed only since 1999, and Medical School programs designed to train specialist physicians (who treat adults) in the research, teaching, and service of health conditions of adults with neurodevelopmental disorders still do not exist. As a result, many health conditions frequently encountered in adults with neurodevelopmental disorders remain undiagnosed and/or improperly treated.

Historical Perspective: Early Services for Adults with Neurodevelopmental Disorders

In the United States, before the 1800’s, there were no specific services for adults with Neurodevelopmental Disorders, who at that time were often inappropriately placed in “almshouses”, “insane asylums”, and jails. Living conditions for these adults were described as that of “filth and degradation” (Scheerenberger 1983) and their lifespans were short. In the late 1800’s, a group of concerned physicians (Seguin, Down, etc.) took interest in this special group of individuals and recognized that placement in “almshouses”, “insane asylums” and “jails” was inappropriate.

They established special facilities, small private residences which provided educational and social supports as well as medical services (Scheerenberger 1983). In 1876, these pioneer physicians also created a professional organization known as the “Association of Medical Officers of American Institutions for Idiotic and Feeble-Minded Persons”. Over the years, the name of this organization sequentially changed to American Association for the Study of the Feeble-Minded (AASFM) in 1906, followed in 1933 to the American Association on Mental Deficiency (AAMD), in 1987 to the American Association on Mental Retardation (AAMR), and in 2006 to the American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities (AAIDD) (www.aaidd.org), a name which exists as of 2023. The AAIDD is the oldest, largest, and most influential professional organization regarding issues effecting the quality of life of persons with ID/DD and has members in 50 countries worldwide.

The changes of name and professional leadership of the AAIDD over the years reflect change in professional composition and mission of the organization. When the AAIDD was first formed in 1876, it was entirely a physician-led medical organization. Physician members were strong advocates and knowledgeable about the social and health conditions experienced by adults with neurodevelopmental disorders and were considered the “experts” in the field at that time (Scheerenbrger 1983, Jirik 2019). As these successful physician-operated facilities grew, many were taken over by local and State governments. Unfortunately, the success of those early small private facilities in the late 1800’s eventually, by the 1930’s, led to massive overcrowding in, then State-operated, residential facilities (SORF’s). Other than custodial care, there was little support from State governments for innovations in social, educational, vocational, or healthcare services, and no Federal support.

“Superintendents” of those large and overcrowded State “institutions” of the 1930-1960’s were usually physicians (often psychiatrists) who were not politically and financially able to maintain high-quality services (both health and non-health related) regardless of efforts of many of these physicians to do so. In 1933 the name of the American Association for the Study of the Feeble- Minded (AASFM) was changed to the American Association on Mental Deficiency (AAMD) which reflected the beginning of a new “social” focus (rather than “health”) on services for children and adults with neurodevelopmental disorders. In the 1940-1950’s many Presidents of the AAMD (AAIDD) were not physicians, and by the 1960’s and beyond few presidents of the AAIDD were physicians.

By the 1960’s various investigations and reports began to reveal the lack of services and deplorable conditions of State-operated institutions. Members of the AAIDD (known as AAMD at that time), as well as family members (e.g., Elizabeth Boggs, PhD), and other interested parties (e.g., Arc, founded 1952) began to advocate for change. In 1961 President John F. Kennedy established a “President’s Panel” to improve services for children with ID/DD (Shorter 2000). This led, in 1963, under the leadership of Robert E. Cooke MD, Chairman of the Department of Pediatrics at Johns Hopkins Medical School in Baltimore, Maryland, and others, to the creation of the “Mental Retardation Facilities and Community Health Centers Construction Act” (Shorter 2000). Federal funding established “University Affiliated Facilities (UAF’s)” which were newly constructed units affiliated with University Medical Schools. The emphasis was on improving the health of children with Neurodevelopmental Disorders through teaching, medical research, and evidence-based clinical services (see below for discussion of health-services for children).

While the original intent of the UAF’s was on medical teaching and medical research, over time, the advocacy for educational, residential, vocational, recreational, and other social changes assumed greater importance (May 2002). Thus, there became less federal funding for health-related issues (physician training, medical research, healthcare services, medical Quality Improvement programs) and more funding for social improvements (educational, residential, vocational, recreational). The original UAF’s, which were affiliated with University Departments of Pediatrics, became university research facilities that maintained a focus on social and healthcare issues of children with neurodevelopmental disorders, but with relatively little attention paid to the health issues of adults with ID/DD, a situation that still exists in 2023.

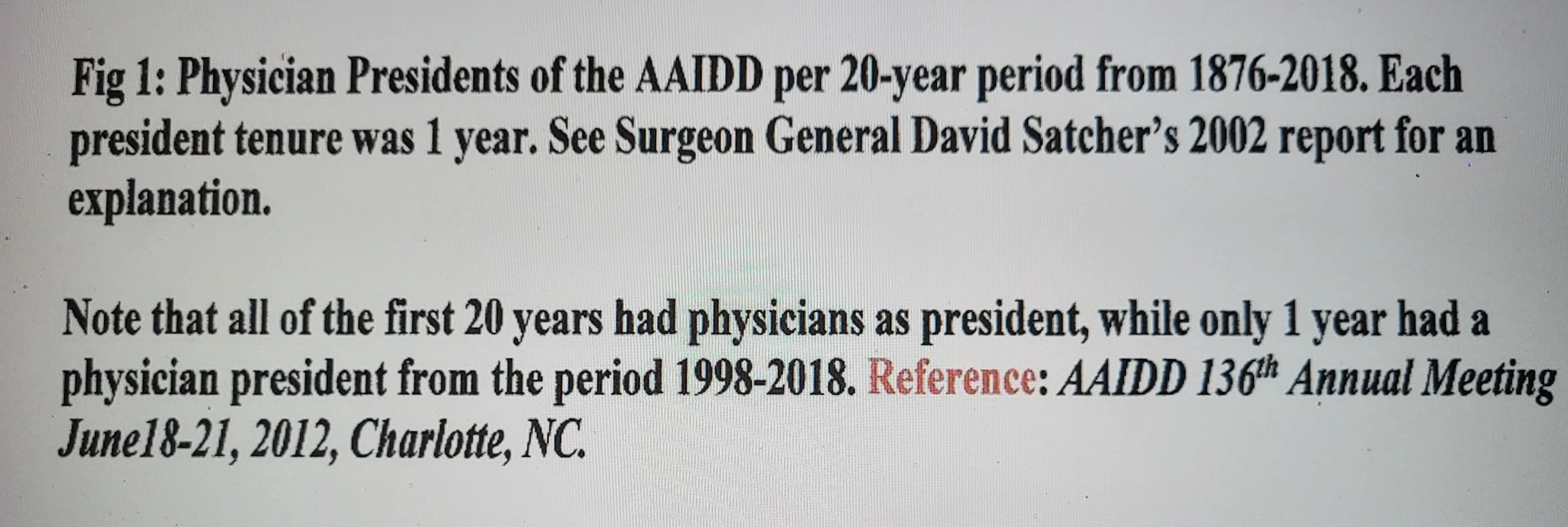

By the 1970’s there were relatively few physician members of the AAIDD (Figure1). Community physicians had little contact with or knowledge about the health status of adults with ID/DD. The pediatric UAF’s (now University Research Centers) continued health-related teaching, research, and service improvements for children with ID/DD. Advocacy for social changes (residential, educational, vocational, recreational), but not health services, became more intense for the now-adults with ID/DD.

Modifications of the Mental Retardation Facilities and Community Health Centers Construction Act of 1963 (see above) led to federal government funding in 1971 of the federal Intermediate Care Facility (ICF) model, which substituted non-physician State officials for physicians regarding administration of specific new services provided in these then large State institutions.

Implementation of the ICF model created a new emphasis in these institutions on improving educational, vocational, social, and residential (but not health) supports which created much needed non-medical services for children and adults. Simultaneously, efforts began to downsize these institutions by transferring residents into small “community” residences (“mainstreaming”). With time. many (but not all) large State ICF’s closed but all were downsized. The ICF government policy of the 1970’s, which removed physicians from federal and state ICF-related policy decisions (because the focus was on non-health related issues) also coincided with further reduction of physicians from any leadership roles in the AAIDD.

Since 1971, Federal and State governmental policy changes, while providing much needed residential, educational, vocational, and recreational services in smaller ICF facilities, community “group homes” and State Medicaid supported “family” homes, have unintentionally contributed to lack of exposure of medical students and medical residents to adults with neurodevelopmental disorders during medical school training.

Understandably, since medical students and medical residents in training rarely saw an adult with a neurodevelopmental disorder, reduction of physician interest in AAIDD membership also occurred (Figure 1).

Health services for many adults with ID/DD became provided by “State Physicians” (who had no special training) in smaller State- operated Intermediate Care residential facilities (ICF’s) which were operated by non-physician Directors or Superintendents, out of the mainstream of conventional medical care and entirely separated from university-based teaching, research, and service. Community-based physicians were completely unprepared to provide quality health services for this medically complex population of adults in the 1970’s.

The DD Act of 1984 (P.L. 98-527) placed even greater emphasis on community-based services and established Councils on Developmental Disabilities, University Centers of Excellence, and Protection and Advocacy Programs (US Department of Human Services 1984). With aggressive downsizing of ICF’s and transfer of adults to small community-based residences in the 1980’s, more health services for adults became provided by well-meaning community-based physicians (usually Family Physicians) who had no training or experience with this special population of adults, simply because such training did not exist. Some Pediatricians would continue to follow their patients with neurodevelopmental disorders into adulthood because families could not identify an “adult” physician to care for them. Internists (both general and specialist) rarely treated these adult patients, and today, primary medical care of adults with neurodevelopmental disorders who do not live in State facilities, is provided primarily by Family Physicians or Pediatricians, and rarely Internists. Standards of care for health services for this special adult population have not been well-defined and are rarely based on evidence-based clinical research.

The DD Act of 2000 reauthorized the concepts of University Centers of Excellence, the Protection and Advocacy System, and Councils on Developmental Disabilities, but with little focus on quality improvement of healthcare, especially for adults with ID/DD. Therefore, even though remarkable improvements had been achieved for non-medical community services, modern generations of physicians who treat only adults (especially Internists and Internal Medicine Specialists) remain relatively unfamiliar with the health conditions that present in adults with neurodevelopmental disorders and many of their health conditions often remain undiagnosed and/or inadequately treated.

Thus, while services for children with ID/DD had dramatically improved (see below for discussion of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics), there continued to be little interest in University-based medical education, “Quality Improvement”, and/or establishment of applied clinical research designed to improve quality of healthcare for adults with ID/DD. Therefore, as of the year 2000, continued inattention to healthcare-related quality improvement created additional problems for adults with ID/DD. As US Surgeon General David Satcher MD succinctly stated in his introduction to the historic Surgeon General’s Report of the Conference in 2001 (published in January 2002) “as services for people with mental retardation evolved, our attention to their health lessened” (US Department of Health and Human Services 2002).

“While services for children with ID/DD had dramatically improved (see below for discussion of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics), there continued to be little interest in University-based medical education, “Quality Improvement”, and/or establishment of applied clinical research designed to improve quality of healthcare for adults with ID/DD.”

Then Secretary of Health and Human Services, Tommy G. Thompson, concluded in the same report, “too few providers receive adequate training in treating persons with mental retardation. Even providers with appropriate training find our current service system offers few incentives to ensure appropriate health care for children and adults with special needs. American health research, the finest in the world, has too often bypassed health and health services research questions of prime importance to persons with mental retardation.” (US Department of Health and Human Services 2002). Lack of proper emphasis on health services (especially for adults) is also reflected in the continued reduction of physician involvement and leadership in the AAIDD (Figure 1).

Following the US Surgeon General’s Conference in 2001 and the subsequent formation of the American Academy of Developmental Medicine & Dentistry (AADMD) in 2002 (Rader 2007; Fenton 2003), the Federal Advisory Committee Report on Training in Primary Care Medicine and Dentistry (the Sixth Annual Report) in 2008 (HRSA, 2008) and the declaration by the American Medical Association in 2010 that persons with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities represented a Medically Underserved Population (MUP) (AMA Report 2010), there has been an awakening appreciation of the physical health conditions that affect adults with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities.

With leadership primarily from Family Medicine, there is now a growing interest in better understanding and treatment of those complex medical, dental, and psychiatric conditions which are frequently encountered in adults with ID/DD (Sullivan 2018). Because of continued “sequestration” of many adults with neurodevelopmental disorders in large and small State-operated and funded residential facilities, Medical Students, Residents, and Fellows as well as Medical School Faculty specialist physicians continue to have little exposure to many adults with medically complex neurodevelopmental disorders. While Family Physicians have taken the lead in improving quality of primary healthcare for adults with ID/DD in the community (Sullivan 2018), important medical research designed to create “evidence-based medicine” for this special adult population remains undeveloped. Thus, community-based mainstreaming of “evidence-based” medical care has not occurred for adults with neurodevelopmental disabilities. Even though, thanks to compassionate Family Physicians, access to community physicians has improved, these community-based Family Physicians remain untrained regarding the evaluation and management of health conditions frequently encountered in adults with chronic neurodevelopmental disabilities (Ankam 2019; Sullivan 2018; Holder 2009). Furthermore, even with access to compassionate and experienced Family Physicians, due to lack of research, a sufficient evidence-base for evaluation and management of many health conditions has still not been established for this population of adults with multiple chronic disabilities (Rader 2007; Sullivan 2018, Keller 2020).

Current Health Services for Children with Neurodevelopmental Disorders: A “Model” for the Adults. While major healthcare-service deficiencies still exist for adults with neurodevelopmental disorders, healthcare-services for children with neurodevelopmental disorders have significantly improved and how these improvements were achieved could serve as a model for improvement for adults with neurodevelopmental disorders.

In addition to the work of UCEDD’s, LENDS and the AUCD (www.aucd.org), health issues of children with neurodevelopmental disorders have greatly benefited from the work of the Society for Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, which was formed in 1982 by eleven University- based Directors of Training Grants provided by the W.T. Grant Foundation of New York City (sdhp.org). The purpose of those training grants was to train Pediatric Residents in how to better care for children with ID/DD. After meeting yearly for five years, from 1977-1982 (required as a condition of funding), these Medical School-based training Directors (all University Professors of Pediatrics) and colleagues created the “Society” for the purposes of continuing to exchange ideas and to encourage research in the field by presenting research papers at its annual meeting, establishing additional training programs, and creation of a Society journal. Thanks to the advocacy of the Society (SDBP), since 1986 the U.S. Maternal and Child Health Bureau of HRSA has provided funding for three-year University-based research/academic Fellowship Programs in the field of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics.

In 1999, due to continued advocacy from the SDBP, the field of Developmental-Behavioral Pediatrics was approved as a subspecialty by the American Board of Medical Subspecialties. The first “Sub Board” of Developmental Behavioral Pediatrics (DBP) within the American Board of Pediatrics was established to collaborate with the Residency Review Committee (RRC) to develop guidelines for subspecialty fellowship training and to develop an examination for certification of subspecialists in Developmental-Behavioral Pediatrics. In October 2002, the first applications for accreditation of Fellowship Programs in DBP were accepted by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME). The first board certification examination in DBP was administered in November 2002, with the first certified subspecialists in the field in March 2003. As of 2008 over three dozen University-based fellowship programs had achieved accreditation by the ACGME. These fellowships are comprised of experiences in patient care designed to lead to the development of clinical proficiency, involvement in community or community-based activities, and development of skills in teaching, program development, research, and child advocacy (sdbp.org). Hundreds of research-trained Board- Certified Specialists in Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics now exist.

Thus, it appears that all the necessary “elements” (teaching curricula, research programs, service delivery by Board-Certified “culturally-competent” Pediatrician Specialists in Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics) for optimal health services for children with neurodevelopmental disorders have been established. Parents who have children with neurodevelopmental disabilities now have access to expert Board-Certified “culturally-competent” physicians who practice evidence-based medicine designed specifically for children with neurodevelopmental disorders. The same cannot be said for adults with neurodevelopmental disorders/disabilities, and parents of children with ID/DD live with constant anxiety about who will be providing healthcare for their children after they become adults.

Health Services for Adults with Neurodevelopmental Disorders

There is now emerging advocacy for creating University/Medical School-based advanced training in “Neurodevelopmental Medicine” for adults with ID/DD (Keller 2020), as has previously been accomplished for children with neurodevelopmental disorders (or ID/DD).

Since adults with neurodevelopmental disorders (NDD) are also subject to the same medical disorders that one encounters in adults without NDD, it is anticipated that the same high medical standards that apply to adults in the general population will be enjoyed by adults with neurodevelopmental disorders as well. However, experienced healthcare professionals who care predominantly for adults with "childhood-onset chronic brain disorders" (i.e., neurodevelopmental disorders) have recognized that certain medical conditions occur more frequently in that population. Because lack of clinical training and absence of literature to guide the medical practitioner still exist for these medically underserved adults, well-defined guidelines (based on evidence-based research) to direct care of these frequently occurring medical conditions (FOMC's) are lacking (Keller 2020).

Examples of FOMC’s include: lack of genetic or acquired etiologic diagnosis, seizures, neuromotor disorders, severe abnormal behavior, recurrent pneumonia, gastrointestinal disorders, osteoporosis, obesity, poor physical fitness/exercise, vitamin D deficiency, oral-health disorders, and polypharmacy (Sullivan 2018, McMahon 2021). These conditions (which occur with different levels of severity and in various combinations) as well as others (such as visual and auditory problems) create a level of complexity to health management of adults with neurodevelopmental disorders which is not appreciated by most providers of primary care medicine. As a result, health services become “fragmented”. An individual may have an undiagnosed genetic syndrome (which needs diagnosis) with seizures managed by one physician (neurologist), gastrointestinal problems by another (gastroenterologist), and abnormal destructive behaviors by a third (Psychiatrist). Poor communication among physicians often results in the use of multiple medications (polypharmacy) which are often not efficacious and associated with undesirable drug-drug interactions and chronic medication toxicities. Relevant clinical research and Fellowship-level training designed to improve health outcomes of adults with neurodevelopmental disorders are needed (Rader 2007; Keller 2020).

“With the initiation of University Affiliated multi-site teaching, research, or Quality Improvement (QI) Adult Health Programs in Internal Medicine and/or Family Medicine for men and women with ID/DD, an evidence-base for practice could begin to form. ”

Internal Medicine might be the most effective “home” for this type of specialized training because of the orientation of Internal Medicine towards specialty-related practice and research. The process could begin by the creation of “Quality Improvement” (QI) Programs (Edwards 2018) in Internal Medicine that focus on the frequently occurring medical conditions, such as obesity, osteoporosis, or lack of physical exercise and etiologic diagnosis. A multi-site network of University- affiliated collaborative QI programs could lead to formation of a new professional organization focused on evidence-based treatment of health conditions that occur frequently in adults with neurodevelopmental disorders. With time, a new medical subspecialty in Neurodevelopmental Medicine might emerge in Internal Medicine, similar to that of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics in Pediatrics. A “Fellowship” level program would create physicians in academic and “tertiary” (specialty) medicine who would serve as consultants to primary-care physicians, perform relevant clinical research, teach other physicians, and help develop (through clinical research) “evidence-based” standards of care for adults with neurodevelopmental disorders (ID/DD).

In support of this concept, Stephen Trumble MD, for his PhD Thesis entitled “Defining the Discipline of Developmental Disability Medicine (Trumble 1998), comprehensively reviewed the issues and barriers in establishing a “Specialty” in adult “Developmental Medicine” and concluded that Internal Medicine, with its specialty orientation towards primary care, might be the most appropriate “home” for a new specialty of adult Neurodevelopmental Medicine. The internist who would choose to specialize in the evaluation and treatment of those health conditions that frequently occur in adults with ID/DD/Neurodevelopmental Disorders, would need additional skills in genetic diagnosis, seizure management, behavior management, and management of motor dysfunction. Thus, any “Fellowship” level training in Neurodevelopmental Medicine for internists would need collaboration with “adult” medical geneticists, neurologists, psychiatrists, and physical medicine & rehabilitation specialists (Trumble 1998).

However, while Internal Medicine might appear to be a logical specialty in which to promote organization of Neurodevelopmental Medicine for adults with ID/DD, there currently appears to be little interest among internists to do so. One survey of U. S. Internal Medicine training programs in 2003 suggested a general lack of awareness, perception of importance, and desire to learn about the complex health conditions encountered in adults with neurodevelopmental disorders (Holder 2003). Regardless of whether they are created in Internal Medicine and/or Family Medicine, teaching, research, and service adult programs need to be created.

These proposed “Adult Health Programs (AHPs)” could be created with funding from various sources such as University Centers of Excellence in Developmental Disabilities, LEND Programs (www.aucd.org), private Foundations, or the Federal Government (HRSA).

Unfortunately, a major barrier to receiving funding from HRSA is the HRSA requirement that the population for which funding is being sought, be designated by strict criteria as a Medically Underserved Population (MUP) (Kornblau 2014). Recently, US Congressman from Massachusetts 6th District, Seth Moulton, has introduced a bill called the Healthcare Extension and Accessibility for Developmentally disabled and Underserved Population Act (or the HEADs UP act of 2018). This bill would designate people with ID/DD as a Medically Underserved Population (MUP). Having the federal Medically Underserved Population (MUP) designation for persons with ID/DD would significantly increase the likelihood that these proposed AHPs would be successful in improving the health outcomes of adults with ID/DD, because medical investigators would then become eligible to apply for HRSA Federal grants which fund programs designed to improve evidence-based teaching, research, and service for those adults who meet the criteria for MUP.

Alternatively, the MUP designation can be obtained in a single State by the Governor’s Exceptional Medically Underserved Population (EMUP) method (Kornblau 2014). “Exceptional MUP Designation States can request designation for a population group that does not score a 62 or below on the IMU (Index of Medical Underservice) and experiences unusual local conditions which are a barrier to access to or the availability of personal health services through the Governor’s Exceptional Medically Underserved Population (EMUP) program. To address unique circumstance, the Governor must make the request for designation to the Secretary of HHS in writing together with local officials. The written recommendation for the designation must describe in detail the unusual local conditions/access barriers/availability indicators which led to the recommendation for exceptional designation and include any supporting data.

In conclusion, with the initiation of University Affiliated multi-site teaching, research, or Quality Improvement (QI) Adult Health Programs in Internal Medicine and/or Family Medicine for men and women with ID/DD, an evidence-base for practice could begin to form. Additionally, these programs would also serve to address the problem of “transitioning” of children with ID/DD into adult medical services. By creating a network of specialized Internists and Family Physicians for adults with ID/DD, these programs would ensure continuity of high-quality healthcare for children with neurodevelopmental disorders after they “age-out” of the pediatric system.

Following the lead of Pediatrics, collaboration of members of individual programs would then lead to creation of a new professional organization of academic physicians designed to promote University-based integrated teaching, research, and service for adults with NDD’s (ID/DD). With time ACGME certification could be obtained, and a new specialty in Neurodevelopmental Medicine established for adults as it was with Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics for children.

About the Author

Philip May MD

Director of Quality Improvement & Research International Foundation for Chronic Disabilities, Inc www.chronicdisabilities.org

Clinical Associate Professor of Medicine (Gratis) University of Louisville School of Medicine Louisville, KY

References

American Medical Association Report of the Council on Medical Service: Designation of the Intellectually Disabled as a Medically Underserved Population (Resolution 805-I-10) CMS Report 3-I-11, Thomas E. Sullivan MD, Chair, 2010.

Ankam N, Bosques G, Sauter C, Steins S, et al. Competency-Based Curriculum Development to Meet the Needs of People with Disabilities: A Call to Action. Academic Medicine. 2019; 94: 781-788.

Association of University Centers on Disabilities (AUCD): Research, Education, Service. www.aucd.org.

Closing the Gap: A National Blueprint to Improve the Health of Persons with Mental Retardation: Report of the Surgeon General’s Conference on Health Disparities and Mental Retardation, U.S Department of Health and Human Services, 2002.

Developmental Disabilities Assistance and Bill of Rights Act (DDAct) History: UCEDD New Directors Orientation; Administration for Community Living, Administration on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Report. 1984.

Edwards J, Mold F, Knivett, D, et al. Quality Improvement of Physical Health Monitoring for People with Intellectual Disabilities: An Integrative Review. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 2018; 62: 199-216.

Fenton S, Hood H, Holder, M, et al. The American Academy of Developmental Medicine and Dentistry: Eliminating Health Disparities for Individuals with Mental Retardation and Other Developmental Disabilities. Journal of Dental Education. 2003; 67: 1337-1344.

Holder M, Gerstman B, & May P. Training Internal Medicine Residents: A Long Ways To Go, EP Magazine. 2003; December: 58-63.

Holder M, Waldman B, & Hood H. Preparing Health Professionals to Provide Care to Individuals with Disabilities. International Journal of Oral Science. 2009;1: 66-71.

Jirik, K. American Institutions for the Feeble-Minded, 1876-1916, PhD Thesis. 2019. https://conservancy.umn.edu/handle/11299/206259

Keller S., Turek G, Asato, M, et al. Complexities of Caring and Transitioning Care for Patients with Intellectual or Developmental Disability. Neurology Reviews (Supplement). 2020: March;124-131.

Kornblau, B. The Case for Designating People with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities as a Medically Underserved Population, ASAN Policy Brief, 2014, https://autisticadvocacy.org/wp- content/uploads/2014/04/MUP_ASAN_PolicyBrief_20140329.pdf

May, P. Personal Interview with Robert E. Cooke MD, Special Olympics Int. Office, Washington, DC. 2002.

McMahon, M & Hatton, C. Comparison of the prevalence of health problems among adults with and without intellectual disability: A total administrative population study. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disability. 2021: https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.12785

Personal Communication. PDF Copy of Healthcare Extension and Accessibility for Developmentally disabled and Underserved Population Act bill description from U.S. Congressman Seth Moulton available on request: philip.may@louisville.edu

Rader R. The Emergence of the American Academy of Developmental Medicine and Dentistry: Educating Clinicians about the Challenges and Rewards of Treating Patients with Special Health Care Needs. Pediatric Dentistry. 2007; 29: 134-137.

Scheerenberger, R. A History of Mental Retardation, Paul H. Brookes Publishing Co. 1983.

Shorter, E. The Kennedy Family and the Story of Mental Retardation. Temple University Press, Philadelphia, 2000.

Society for Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics Website:

https://sdbp.org/about/historical-timeline/

Sullivan W, Diepstra H, Heng J, et al. Primary Care of Adults with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities: 2018 Canadian Consensus Guidelines. Canadian Family Physician. 2018; 64: 254-279.

The Role of Title VII, Section 747 in Preparing Primary Care Practitioners to Care for the Underserved and Other High-Risk Groups and Vulnerable Populations. Sixth Annual Report of the HRSA Advisory Committee on Training in Primary Care Medicine and Dentistry. Rockville, MD, March 2008.

Trumble S, Defining the Discipline of Developmental Disability Medicine, PhD Thesis, Completed 1998, Monash University, Victoria, Australia. (Unpublished). PDF Copy available on request: philip.may@louisville.edu.

US Dept of Health & Human Services training module on Quality Improvement, April 2011, accessed 1/12/21.