E-Cigarettes- A Health Policy Overview

By Kavitha P. Das, BDS, MPH, MS, Parshad Mehta BDS, MPH, Jamie D. Zelig BS, MPH

“An estimated 61.4 million people in the United States, reported having a disability. Students with disabilities in university settings, had a higher rate of tobacco (chewing and smokeless tobacco, cigarettes, cigars, and pipes) use compared to those without disabilities. These students were also almost twice as likely to meet the criteria for nicotine dependence in the past month. ”

Abstract

Electronic cigarette use, commonly known as e-cigarettes or vaping, is defined as inhaling a vapor that may contain nicotine and other chemical substances. An electronic or battery-operated device is used to produce an aerosol or vaper, which is then inhaled. E-cigarette use is considered a major public health concern due to its appeal to young adults. E-cigarettes come in different forms which can look like pens, cigarettes, cigars, pipes, and USB flash drives, and are offered in a variety of flavors, both of which are attractive to young people. This paper will address e-cigarette use among young adults and its relationship to the adverse health outcomes vaping can cause and includes a review of global and United States policies and regulations and suggested recommendations for future change in policies and practices. Additionally, information on people with disabilities and e-cigarette use is included.

Since e-cigarettes do not always resemble traditional cigarettes, they can be easily hidden. The flavors mask the smell of cigarette smoke and make it difficult for parents and teachers to detect. Studies show that E-cigarette use is increasing among middle school and high school students and is the most common form of tobacco use among young adults. As of 2021, 1.73 million high school students and 320,000 middle school students are using e-cigarettes.

Reports indicate that adolescents and young adults with intellectual disabilities exhibit higher e-cigarette usage compared to those without cognitive disabilities.[1] There is also evidence that young people who use e-cigarettes are more likely to smoke conventional cigarettes in the future. E-cigarette use is unsafe as it can contain nicotine, volatile organic compounds, cancer-causing chemicals, heavy metals, and ultrafine particles which are inhaled into the lungs. This can lead to harmful health outcomes, especially during adolescence, when exposure to these chemicals can harm the developing brain. Addiction to e-cigarettes can cause adverse effects when trying to stop, such as withdrawal symptoms and irritability.

Globally, only 68 countries regulate the sale of e-cigarettes, and 25 countries have banned its sale. Three countries, the US, Russia, and Germany, account for the most sales at 60%, yet the US leads in revenue from sales of e-cigarettes at $8.2 billion. In the US, the Food and Drug Administration is addressing e- cigarettes and their adverse health effects through legislation to regulate the manufacture, distribution, and marketing of tobacco products, of which e-cigarettes are considered.

The increasing rise of e-cigarette use among adolescents and the adverse health outcomes that can occur are being addressed globally and in the US through changes in policies and regulations. Implementation of laws limiting e-cigarette sales that include flavorings, the chemical makeup of the e-cigarettes, advertising, and marketing to youth through social media platforms are being enacted throughout the 50 states and in other countries.

Introduction

The American Lung Association declares e-cigarette use among U.S. youth and young adults as a major public health concern.[2] The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention describes various forms of e-cigarettes as e-cigs, vapes, e-hookahs, vape pens, and electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS). Some e-cigarettes look like regular cigarettes, cigars, or pipes. Some look like USB flash drives, pens, and other everyday items.[3] These devices are the most common forms of nicotine used by teenagers and young adults in the United States. Vapes are devices that are battery-operated and are used to inhale an aerosol or vaper, which typically contains nicotine (not always), flavorings, and other chemicals.[4] Existing data suggest that teenagers and young adults with intellectual disabilities have a higher prevalence of using nicotine-containing e-cigarettes compared to those without cognitive disabilities.[5]

“In December 2023, the World Health Organization issued a pressing appeal regarding e-cigarettes to mitigate the dangers associated with their use, especially targeting individuals who have never smoked, adolescents, and young adults”

Background

E-cigarettes were first introduced to the U.S. and Europe in 2006, and it is reported that they were marketed as a harm reduction device.[6] However, the US Food and Drug Administration explicitly states that “no e-cigarette has been approved as a cessation device or authorized to make a modified risk claim and more research is needed to understand the potential risks and benefits these products may offer adults who use tobacco products”.[7] K Jones et al. reported that vapes can serve as a “gateway” to nicotine addiction and lead to smoking cigarettes.[8] Researchers have reported a significant increase in e-cigarette use by adolescents and a study reported that 99% of e-cigarettes sold in the United States contain nicotine.[9]

As vapes do not always look like traditional cigarettes, it is easier for teenagers to conceal them. Flavored vapes aid in concealing the odor of traditional cigarettes, and they are less likely to be detected by parents and teachers. A 2021 study reports that an estimated 11.3% (1.72 million) of high school students and 2.8% (320,000) of middle school students stated current use of e-cigarettes. Flavored e-cigarettes are the most popular form of tobacco product used by teenagers – 85 percent.[10] As early as 2014, it was reported that e-cigarettes were the most commonly used tobacco product among adolescents in the United States.[11] In 2020, TW Wang et al published a report where 3.6 million middle and high school students reported current e-cigarettes use and more than 80% of current users reported flavored e-cigarette use.[12]

The use of tobacco products by youth, including e-cigarettes, is unsafe. Most e-cigarettes contain nicotine, and nicotine exposure during adolescence can harm the developing brain according to a US Surgeon General Report from 2016.[13] There is incontrovertible evidence of the harmful effects of tobacco on the body.

Evidence on the adverse effects of nicotine exposure in conventional cigarettes, including addiction, and other harmful effects, are specifically relevant to e-cigarettes. However, nicotine quantities in e-cigarettes vary tremendously. A seasoned cigarette smoker responds differently to nicotine in e-cigarettes compared to a nonsmoker versus a teenage smoker. More studies are needed to study the impact of nicotine and other chemicals in e-cigarettes in youth.

Research studies in adults have found the amount of nicotine from e-cigarettes is in varying doses ranging from slight to as large.[14] Evidence from several decades has demonstrated nicotine as a highly addictive chemical compound that can change the way the brain works and cause physical and psychological dependence. In addition to the known harmful effects of nicotine, e-cigarettes also contain various chemicals that can be potentially toxic. Users of e-cigarettes are exposed to a variety of aerosolized chemicals, flavorings added intentionally to e-liquids, adulterants added unintentionally, and other toxic substances produced during the heating and aerosolization process. The toxic substances in e-cigarette aerosol are not well understood, though several are known carcinogens. According to the American Cancer Society, some of the chemicals formed in e-cigarettes are propylene glycol (increase irritation of the lungs and airways after concentrated exposure), formaldehyde (a cancerous substance that may form if the e-liquid overheats or not enough liquid reaches the heating element), and metals that have been linked to cancer (lead, nickel, chromium, manganese, and arsenic).[15]

An estimated 61.4 million people in the United States, reported having a disability.[16] Students with disabilities in university settings, had a higher rate of tobacco (chewing and smokeless tobacco, cigarettes, cigars, and pipes) use compared to those without disabilities. These students were also almost twice as likely to meet the criteria for nicotine dependence in the past month.[17] The existing research on disability-related variances in tobacco consumption primarily focuses on cigarette and other tobacco product usage, with limited exploration on e-cigarette use among young adults with disabilities. In 2020, the Center for Disease Control and Prevention reported a higher use of vapes in adults with disabilities (8%) when compared to adults without disabilities (3.9%).[18] In a study by A Senders et al, on disparities of tobacco use in adolescents in the state of Oregon USA, it was reported that 18.3% of adolescents with disability used e-cigarettes when compared to 12.3% with no disability.[19] An article published by E Emerson in 2023, reported that there was a tentative higher prevalence of e-cigarette use among female adolescents with intellectual disability at the age of 17 when compared with girls with no disability of the same age. He recommended additional studies in this population.[20]

Policy on E-Cigarettes

Global Policy on E-Cigarettes

RD Kennedy et al., reported in a global study on policies and regulations on e-cigarettes, that only 68 countries regulated e-cigarettes in 2017 and 25 countries banned the sale of e-cigarettes.[21] The global revenue from e-cigarette sales was estimated to be $3.5 billion in 2015.[22] Sixty percent of the global sales were in USA, Russia, and Germany. In contrast, in 2023, the revenue in the United States alone was reported to be $8.2 billion. When compared to global sales, the largest revenue in 2023 is generated in the US.[23] The World Health Organization’s Tobacco Free Initiative released a report on e-cigarette surveys completed by 90 countries. E-cigarettes were classified as tobacco products in 22 countries; 12 countries classified them as therapeutic products and 14 countries classified them as consumer products.[24] The taxation of e-cigarettes or liquids was reported in very few countries. In most countries where e-cigarettes were sold, minimum age for sale, regulations on indoor use in public spaces, restrictions on advertising and promotion, regulations on ingredients and flavors, and nicotine concentration were regulated. All European countries have implemented policies to address flavorings in e-cigarettes. Some countries require a prescription to buy e-cigarettes as they were marketed as a harm-reduction method for smokers trying to quit smoking. In Australia, it is illegal to use, sell or buy nicotine for use in e-cigarettes without a prescription. [25]

In December 2023, the World Health Organization issued a pressing appeal regarding e-cigarettes to mitigate the dangers associated with their use, especially targeting individuals who have never smoked, adolescents, and young adults.[26]

USA Policy on E-Cigarettes

To protect the public and create a healthier future for all Americans, the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act (Tobacco Control Act), signed into law on June 22, 2009, gives FDA authority to regulate the manufacture, distribution, and marketing of tobacco products.[27]

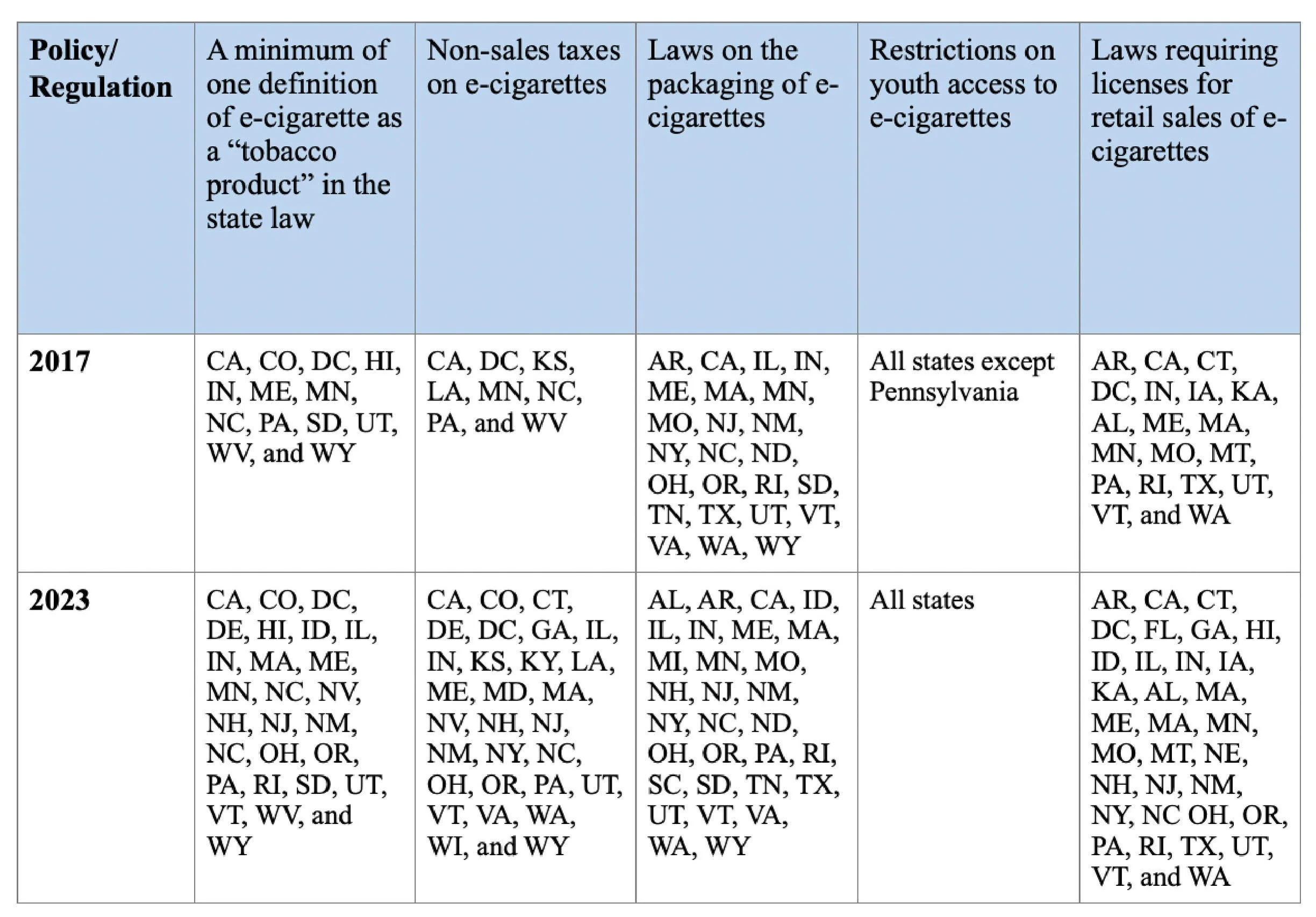

In 2017, the Public Health Law Center published a review of policies on e-cigarettes in the US categorized by 50 states and Washington DC.[28] This has been updated to reflect the changes in 2023.[29] Twenty-five states included a minimum of one definition of e-cigarette as a “tobacco product” in their state law in 2023. This definition was included in only 13 states in 2017. In 2017, only eight states had non-sales taxes on e-cigarettes. In 2021, this rose to 30 states. In 2023, 30 states had laws on the packaging of e-cigarettes compared to 24 states in 2017. All states had restrictions on youth access to e-cigarettes except Pennsylvania in 2017. In 2023, Pennsylvania also had policies in place for the restriction of e-cigarettes to youth. In 2017, 19 states had laws requiring licenses for retail sales of e-cigarettes. This increased to 33 in 2023 and FL, GA, HI, ID, IL, MA, NE, NH, NJ, NM, NY, NC, OH, and OR, also enacted laws requiring licenses for retail sales of e-cigarettes. Delaware only required a license to sell e-cigarette liquid and not the e-cigarette device. See Table 1.

Table 1:

To decrease and prevent smoking among individuals with disabilities, the Center for Disease Control and Prevention recommends that public health programs should include disability in national and local surveys and research efforts and create tailored smoking cessation messages for individuals with disabilities in public health messaging and programs on tobacco cessation.

The American Cancer Society and the American Cancer Society Cancer Action Network, support several vital policy measures to reduce youth e-cigarette use. They recommend that the FDA must effectively regulate [30]

a. All e-cigarettes

b. Enforcing premarket reviews

c. Restricting advertising and marketing to protect youth

d. Preventing the dissemination of false and misleading messages and imagery

e. Requiring strict product standards

f. All substances in tobacco products, including flavoring chemicals and nicotine,

g. Testing of all substances used in e-cigarettes.

h. The safety of the devices too.

They recommend prohibiting the use of all flavors, including mint and menthol, in all tobacco products, including e-cigarettes. Additionally, the FDA should reduce nicotine in all combustible tobacco products to non-addictive levels and firmly limit the amount of nicotine permitted in e-cigarettes.

Conclusion

Reports suggest e-cigarette use increases an individual's chance of using combustible cigarettes. There has been a shift in health policies and regulations on e-cigarettes globally and in the United States of America. More states in the USA have laws regulating various areas pertaining to e-cigarette sales, flavoring, chemical makeup, youth access, and advertising. However, the steep rise in the use of e-cigarettes use particularly among the youth in the United States warrants the immediate implementation of additional policies that restrict the sales of these products to youth and ban the sale of all forms of flavored e-cigarettes including menthol, mint, and wintergreen flavors. Independent recommendations and resources must be made to address the use of e-cigarettes in individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Funding must be made available for well-designed longitudinal studies on e-cigarettes and their impact on the human body with a focus on youth and as a harm reduction device for heavy smokers of combustible cigarettes.

References

[1] Wells MB. Tobacco Use in Adolescents With Disabilities: A Literature Review. Subst Abuse. 2023;17:11782218231179599. Published 2023 Jun 27. doi:10.1177/11782218231179599

[2] American Lung Association. E-cigarettes & vaping. Lung.org. Accessed April 7, 2023. https://www.lung.org/quit-smoking/e-cigarettes-vaping

[3] CDC Tobacco Free. Electronic cigarettes. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Published April 8, 2022. Accessed April 15, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/basic_information/e-cigarettes/index.htm

[4] National Institute on Drug Abuse. Vaping devices (electronic cigarettes) DrugFacts. National Institute on Drug Abuse. Published January 8, 2020. Accessed April 7, 2023. https://nida.nih.gov/publications/drugfacts/vaping-devices-electronic-cigarettes https://nida.nih.gov/publications/drugfacts/vaping-devices-electronic-cigarettes

[5] Gimm G, Schulz JA, Rubenstein D, Casseus M. Examining the prevalence of nicotine vaping and association of major depressive episodes among adolescents and young adults by disability type in 2021. Addict Behav. 2024;152:107975. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2024.107975

[6] Hajek P, Etter JF, Benowitz N, Eissenberg T, McRobbie H. Electronic cigarettes: review of use, content, safety, effects on smokers and potential for harm and benefit: Electronic cigarettes: a review. Addiction. 2014;109(11):1801-1810. doi:10.1111/add.12659

[7]Center for Tobacco Products. E-cigarettes, vapes, and other electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS). U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Accessed April 7, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/tobacco-products/products-ingredients-components/e-cigarettes-vapes-and-other-electronic-nicotine-delivery-systems-ends

[8] Jones K, Salzman GA. The vaping epidemic in adolescents. Mo Med. 2020;117(1):56-58.

[9] Marynak KL, Gammon DG, Rogers T, Coats EM, Singh T, King BA. Sales of nicotine-containing electronic cigarette products: United States, 2015. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(5):702-705. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2017.303660

[10] Park-Lee E, Ren C, Sawdey MD, et al. Notes from the field: E-cigarette use among middle and high school students - national youth tobacco survey, United States, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(39):1387-1389. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7039a4

[11] Office on Smoking and Health at A glance. Cdc.gov. Published November 10, 2022. Accessed April 7, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/resources/publications/aag/tobacco-use.htm

[12] Wang TW, Neff LJ, Park-Lee E, Ren C, Cullen KA, King BA. E-cigarette use among middle and high school students—United States, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020;69:13102. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6937e1

[13] CDC. E-cigarette use among youth and young adults. A report of the surgeon general. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC, Office on Smoking and Health; 2016. https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/sgr/e-cigarettes/pdfs/2016_sgr_entire_report_508.pdf

[14] Lopez AA, Hiler MM, Soule EK, et al. Effects of electronic cigarette liquid nicotine concentration on plasma nicotine and puff topography in tobacco cigarette smokers: A preliminary report. Nicotine Tob Res. 2016;18(5):720-723. doi:10.1093/ntr/ntv182

[15] What do we know about E-cigarettes? Cancer.org. Accessed April 18, 2023. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/risk-prevention/tobacco/e-cigarettes-vaping/what-do-we-know-about-e-cigarettes.html

[16] Atuegwu NC, Litt MD, Krishnan-Sarin S, Laubenbacher RC, Perez MF, Mortensen EM. E-Cigarette Use in Young Adult Never Cigarette Smokers with Disabilities: Results from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Survey. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(10):5476. Published 2021 May 20. doi:10.3390/ijerph18105476

[17] Casseus M, Graber JM, West B, Wackowski O. Tobacco use disparities and disability among US college students. J Am Coll Health. 2022;70(7):2079-2084. doi:10.1080/07448481.2020.1842425

[18] Cigarette Smoking Among Adults with Disabilities. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Last reviewed November 19, 2020. Accessed March 28, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/disabilityandhealth/smoking-in-adults.html

[19] Senders A, Horner-Johnson W. Disparities in E-Cigarette and Tobacco Use Among Adolescents With Disabilities. Prev Chronic Dis. 2020;17:E135. Published 2020 Oct 29. doi:10.5888/pcd17.200161

[20] Emerson E. Brief report: the prevalence of smoking and vaping among adolescents with/without intellectual disability in the UK. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2023;67(11):1190-1195. doi:10.1111/jir.13072

[21] Kennedy RD, Awopegba A, De León E. De León E, et al Global approaches to regulating electronic cigarettesTobacco Control 2017;26:440-445. et al capproaches to regulating electronic cigarettes Tobacco Control. 2017;26:440-445.

[22] Mincer J. E-cigarette usage surges in past year: Reuters/Ipsos poll. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-ecigarette-poll-analysis-idUSKBN0OQ0CA20150610. Published June 10, 2015. Accessed May 14, 2023.

[23] E-Cigarettes - United States. Statista. Accessed May 14, 2023. https://www.statista.com/outlook/cmo/tobacco-products/e-cigarettes/united-states

[24] Conference of the parties to the WHO framework convention on tobacco control. Who.int. Published 2014. Accessed May 14, 2023. http://apps.who.int/gb/fctc/PDF/cop6/FCTC_COP6_10-en.pdf?ua=1

[25] E-cigarettes and vaping. Lung Foundation Australia. Published December 2, 2020. Accessed April 8, 2023. https://lungfoundation.com.au/lung-health/protecting-your-lungs/e-cigarettes-and-vaping/

[26] Technical note on the call to action on electronic cigarettes. World Health Organization. Published on 14 December 2023. Accessed March 28, 2024. https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/technical-note-on-call-to-action-on-electronic-cigarettes

[27] Family smoking prevention and tobacco control act - an overview. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Accessed April 18, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/tobacco-products/rules-regulations-and-guidance/family-smoking-prevention-and-tobacco-control-act-overview

[28] U.S. e-cigarette regulations - 50 state review. Publichealthlawcenter.org. Accessed April 15, 2023. https://www.publichealthlawcenter.org/resources/us-e-cigarette-regulations-50-state-review

[29] U.S. e-cigarette regulations – 50 state review. Harvard.edu. Accessed April 15, 2023. https://repository.gheli.harvard.edu/repository/collection/resource-brief-e-cigarettes-and-health/resource/12962

[30] American cancer society position statement on electronic cigarettes. Cancer.org. Accessed April 28, 2023. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/risk-prevention/tobacco/e-cigarettes-vaping/e-cigarette-position-statement.html

About the Authors

Kavitha P. Das, BDS, MPH

Jamie D. Zelig BS, MPH

Parshad Mehta BDS, MPH